Introduction

The American physicist Richard Feynman once said:

“If we were to name the most powerful assumption of all, which leads one on and on in an attempt to understand life, it is that all things are made of atoms…”

So it is promising that nowadays, almost everyone who has passed through their education is familiar with the idea that objects are made of tiny particles called “atoms”. This concept is so well-known it has become part of modern culture. Most people will probably also remember from their early science lessons that there are numerous different types of atoms and that these are organised into the periodic table and given symbols that make good questions on quiz shows.

However, fully appreciating just how incredibly tiny these atoms are is not so easy and isn’t something that you can relate to common experience. If atoms are so small, how many are there in a coin, a human being or a swig of water from your bottle? What exactly is it that makes atoms different to one another? What are atoms made of themselves – even smaller things? And how on earth did anyone find all this out? If you are going to make progress as a chemist you will need to think about questions like these and try to comprehend the answers. Not only will it help your A-level chemistry but it will help you understand the significance of one of mankind’s great discoveries.

The size of atoms

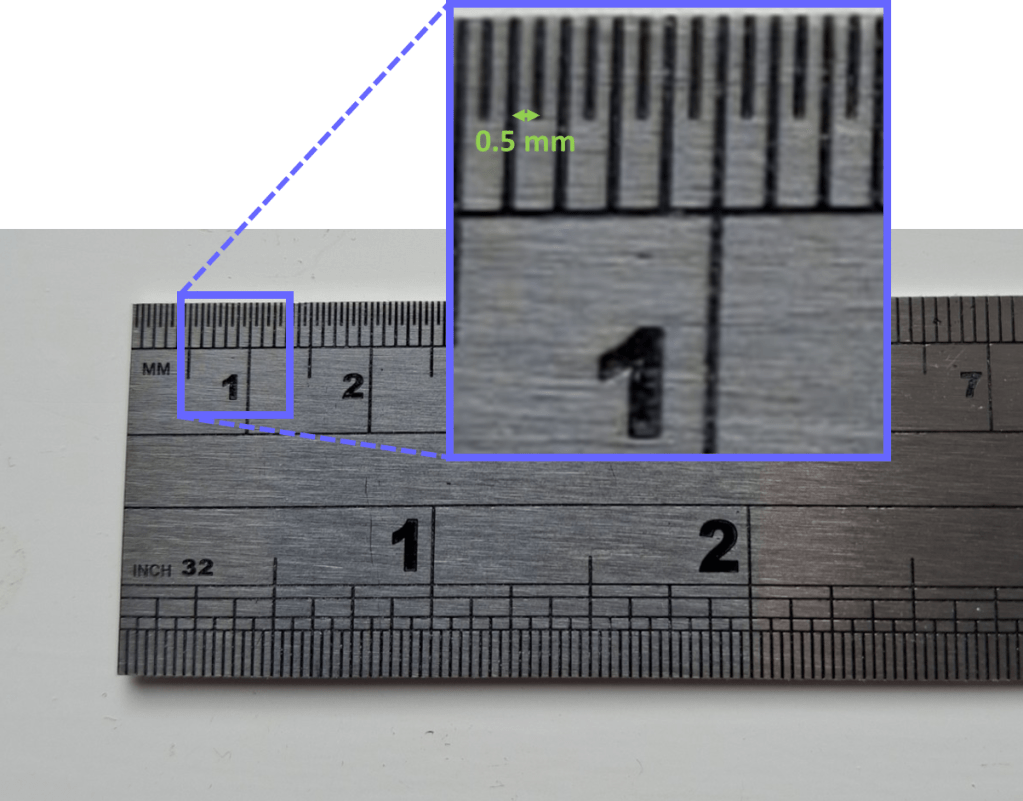

Atoms are so incredibly small that the kind of units we use in everyday life are not really suitable to describe them. For example, look at the smallest distance marked on a ruler which is usually 1 mm. Here is the one on my desk which even has 0.5 mm divisions at one end:

It’s a steel ruler, so most of the atoms in it are iron, and a fairly simple calculation reveals that you could line up almost 2 million iron atoms end-to-end across that small distance.

If we imagine atoms as spheres, an iron atom has a diameter of about 2.52 x 10-10 m, which is equal to 2.52 x 10-7 mm (0.000000252 mm). These are both staggeringly small and fairly awkward numbers to use and, consequently, m and mm aren’t much use when you are thinking about atoms.

Therefore chemists tend to use other units instead. Three common units for this kind of work are:

Nanometre, nm:

1 billionth of a metre so that 1.0 m = 1.0 x 109 nm.

500,000 nm would fit across the smallest 0.5 mm divisions of my ruler.

Picometre, pm:

1 thousandth of a billionth of a metre so that

1.0 m = 1.0 x 1012 pm.

This means that a picometre is a thousandth of a nanometer and 1.0 nm = 1000 pm.

Angstrom, Å: (sometimes also written using the Swedish alphabet as Ångström):

One angstrom is a tenth of a nm, so that 1.0 m = 1.0 x 1010 m

In these units, the dimensions of atoms become a little more manageable; the iron atoms described above have a diameter of 252 pm equal to 0.252 nm and 2.52 Å. These are somewhat easier numbers to handle and compare with others in your head.

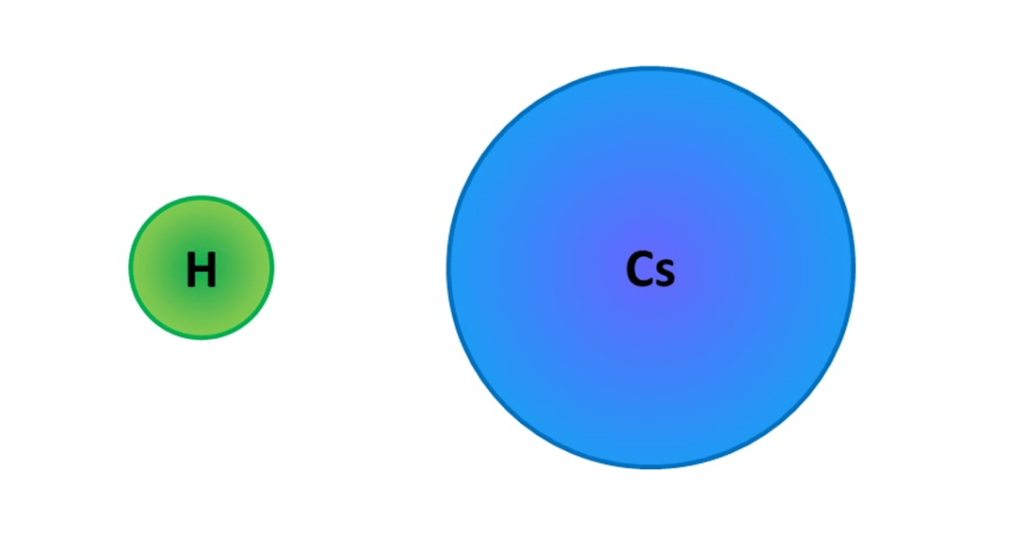

Not all atoms have the same size and there are patterns in the diameter / radius of atoms and the position of an element in the periodic table. This is a key idea in many areas of chemistry will be discussed further in later sections (links will be inserted here when available). There are also numerous different methods for measuring the diameter of atoms and sometimes average values are used, so you will not always find the same numbers quoted. I will write more about this on a later page. However, for the time being I will use something called the “van der Waals radius” which means we can imagine atoms as solid spheres and we’ll return to defining radii better in future sections (and find out that atoms don’t have hard edges anyway!). Under this system, the smallest atoms are hydrogen and helium from the top row of the periodic table, with radii of a just over 100 pm and the largest I could find measurements for are caesium and francium, caesium having a radius of 343 pm. The diagram shows the sizes of hydrogen and caesium atoms to scale:

None the less, all atoms really are incredibly tiny and you’ve got absolutely no chance seeing them with an optical microscope of the sort you might use in a school or college lab. Those instruments might possibly enable you to see objects around the 1000 nm scale, but that is still nowhere near enough to distinguish individual atoms.

The mass of atoms

Given the tiny size of atoms it will no come as no surprise to learn that they also have incredibly small masses and, again, everyday units are not well suited to describing them. For example, a hydrogen atom has a mass of 1.67 x 10-27 kg, which can be written as:

0.00000000000000000000000000167 kg

It’s even hard to tell by looking whether there are actually enough zeros in that number or not, I’ve had to count them several times when typing this page. Even the most massive atoms are only around 300 times heavier than a hydrogen atom, which still involves an impractical string of zeros. Obviously, trying to use numbers like this is unappealing, so chemists use a relative mass unit, where the masses of atoms are compared to a standard (the mass of 12C). On this scale hydrogen atoms have a mass of 1.0080, which is a lot easier. This will be discussed further in later sections (links will be inserted here when available).

Discovery of atomic structure

Now, if you think atoms are small, wait until you find out about a set of ingenious experiments carried out over a short period of time from the late 1890s until the early 1930s. These are described in the next few sections (links will appear here when available). The results of these experiments demonstrated that atoms could not really be regarded as hard, indivisible spheres, because they are in fact constructed from a number of even smaller “sub-atomic” particles. This led to the astonishing realisation that almost all the mass of an atom is compressed into a miniscule nucleus (with a diameter many thousands of times smaller than a whole atom) and that consequently most of an atom (and therefore, most of everything) is completely empty space!

“Copyright Simon Colebrooke 10th October 2024″

Suggested next pages

To start reading about the discovery of atomic structure go to Section 1.2 on the discovery of the electron.

Alternatively, click the icons below to either return to the homepage, or try a set of questions on this topic (choose the Q icon) or return to the notes menu (N icon).

Update history:

Minor text modifications and diagram of H and Cs atoms added 26th March 2025.

Minor text modifications 7th April 2025.