In this section find out about the experiments JJ Thomson carried out to study cathode rays and conclude they were negatively charged particles – electrons – contained inside all atoms. His Plum Pudding model developed to explain this conclusion is described.

Background

To an extent, the idea of objects being made from atoms can be traced back to ancient Greece. The philosopher Democritus, who lived there around 2,500 years ago, was prominent among a group proposing this view, suggesting that everything was made of tiny, indestructible atoms, that could connect together to form different objects. Indeed, the English word “atom” is derived from the original Greek for “indivisible” as they were thought to be the smallest units of matter and couldn’t be further divided. However, this concept wasn’t based on what we would now consider science as there was no experimental evidence. Never the less, hundreds of years later the word “atom” was eventually adopted by chemists but with the foundation of results from experiments. Important in this process was John Dalton, who put forward his atomic theory in the mid 1800s (a link to the Dalton page will appear here). By studying the masses of different elements which combine together, Dalton concluded that atoms were not all the same and atoms from different elements had different masses. The exact structure of atoms though, remained unknown.

JJ Thomson

A series of experiments around the turn of the 20th century completely changed what was known about atoms. The first batch of these was by a Professor in the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge UK; JJ Thomson. He was interested in studying “cathode rays” which were a well-known phenomenon seen when a voltage was applied across two electrodes in a vacuum tube (a glass tube with all the air pumped out). The cathode rays could be deflected by a magnet and appeared to be related to electric charge.

At the time, there were conflicting opinions about the nature of cathode rays; were they negatively charged particles or were they instead linked to the mysterious medium called the “aether” that was thought to fill space and allow light to travel through a vacuum? Thomson thought they were more likely to be negative particles and so set out to characterise their behaviour.

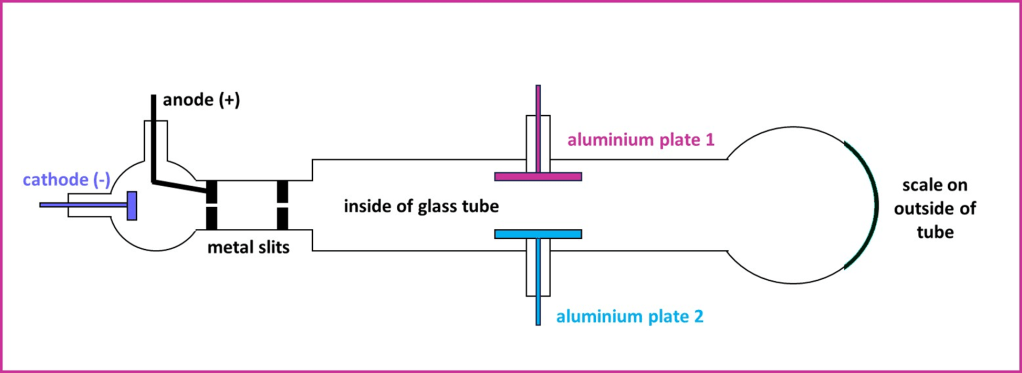

Thomson investigated the effect of electric and magnetic fields on these cathode rays and measured the deflection in their path that was produced. A representation of one of his experimental setups is shown in the diagram below:

Diagram 1: One piece of apparatus used by Thomson to discover the electron.

The analysis of his results was somewhat complicated by the influence of traces of gases inside the tube, but he was able to make some important measurements that are fairly easy to understand:

1. When aluminium plate 1 at the top of the apparatus was given a positive charge (and aluminium plate 2 a negative charge), the cathode ray was deflected upwards. The situation was reversed when plate 1 was negative; in this case the rays were deflected downwards by an equivalent amount. Under the influence of magnetic fields the cathode rays still behaved as predicted for negative particles. Thomson could not separate any negative particles from the rays by using magnetic or electrically charged plates – the conclusion was that the rays were actually a stream of negatively charged particles.

2. Assuming now that they were particles, Thomson attempted to measure the “mass to charge” ratio of the cathode rays. This is the mass of a particle divided by the charge. He obtained some very small values of around 0.5 x 10-7, which was much smaller than the values in the region of 10-4 which had been found for the hydrogen ion and other ions in electrolysis. Based on how far the cathode rays would travel through different gases, Thomson believed that the small mass to charge ratio implied the particle had incredibly small mass. This led him to the astonishing conclusion that the mass was less than a thousandth of that of a hydrogen atom – which up until that point had been the lightest known particle.

3. Cathode rays with the same properties (extent of deflection and mass to charge ratio) were produced from different metal cathodes (Al, Pt and Fe) and in different experiments where the gas inside the glass tube was altered. This implied that the new particles were present in all materials and so could be considered “universal”.

Thomson decided the that cathode rays, which were actually a stream of negative particles, were coming from within the atoms in the cathode. This meant that atoms were not indestructible after all, but were actually made up from smaller objects combined in some way. In 1897 Thomson gave these new particles the strange sounding name “corpuscles”, although the word “electron” quickly became more widely used (which is fortunate as it sounds a lot less like the kind of thing you ought to show your doctor!).

Thomson detected particles with the same mass to charge ratio in other situations involving electrical discharges, implying that they were a common source of electrical charge. Further experiments with ionised gases led him to conclude that ionisation meant the removal of a corpuscle / electron. These discoveries were outlined in three scientific papers in 1897, 1898 and 1899 and were the first indicating that atoms were composed of much smaller sub-atomic particles.

Plum Pudding Model

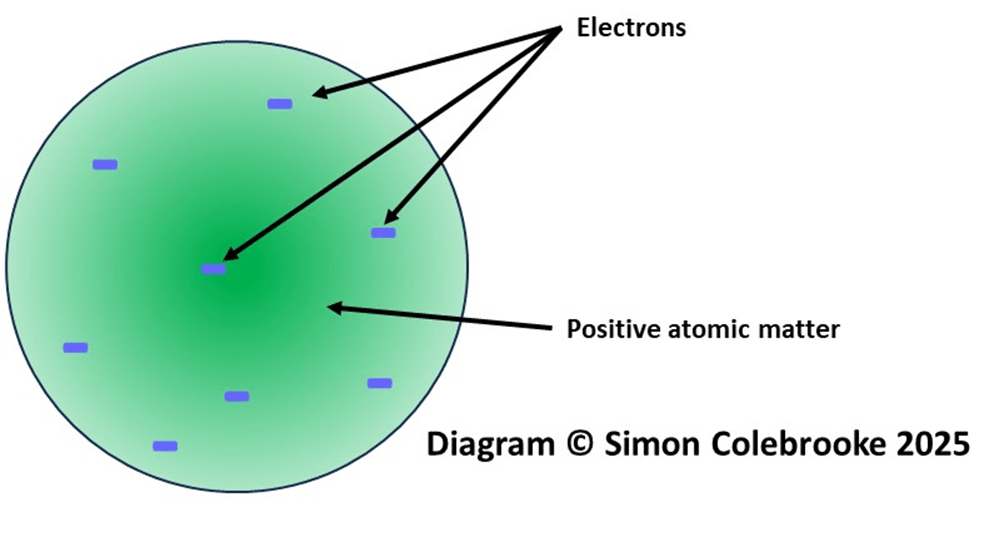

The discovery of the electron showed that atoms were not indivisible objects, but had some internal structure. Over the next few years, Thomson developed a model for the atom, which consisted of a sphere of positive matter with electrons embedded in it. He also speculatively suggested some possible arrangements for the electrons. The positive matter was required in order for atoms to be neutral overall. Thomson probably never referred to it this way himself, but the model is often called the “Plum Pudding Model” in an analogy to the popular desert of a sponge cake with raisins spread through it; the raisins represent the electrons, and the sponge the remaining positive matter. I have sketched a version below, without giving any specific arrangement to the electrons.

The plum pudding model was quite limited as nothing was known about the nature of the positively charged matter or the distribution and number of electrons within the atom. However, the tiny mass of the electrons implied that most of the mass of an atom was in the form of something else, which sets the scene for the next developments.

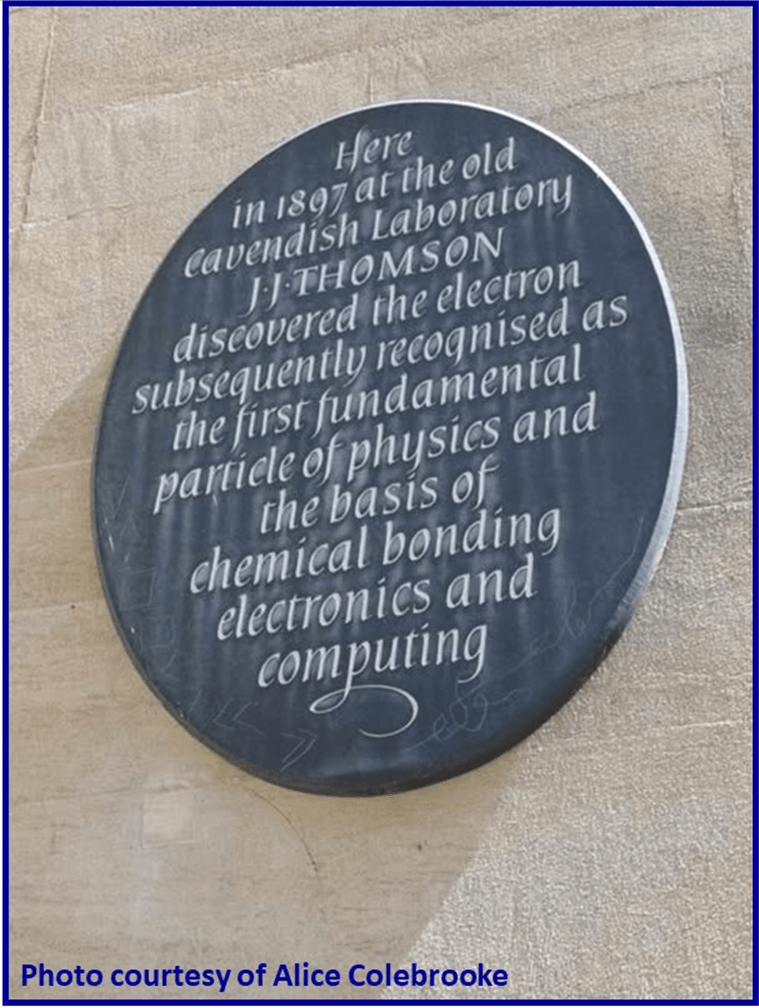

If you walk down Free School Lane in Cambridge today, past the location of the old Cavendish Laboratory (and that is often a good move because it’s relatively free of tourists) you’ll be able to see a small sign commemorating Thomson’s work. It mentions the electron as “…the basis of chemical bonding, electronics and computers“. Slightly under-stated in my opinion given not only the significance of the discovery that atoms can be broken apart into smaller things, but the fact that almost all of chemistry that has followed relies on electrons!

Copyright Simon Colebrooke 16th October 2024.

Suggested next steps:

Think about the key ideas from this section about – try to summarise them as a set of bullet-points and click here to see if you’ve chosen the same as me.

Answer the questions by clicking on the green “Q” below.

Continue reading about atomic structure in chronological order: go to Section 1.3 and the discovery of the nucleus.

To read more about electron arrangements: Section 1.9 and electron orbitals, sub-shells and energy levels.

In writing this article I have referred to the paper written by JJ Thomson in 1897 titled “XL. Cathode Rays” and published in the Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. Much of it is quite readable for an A-level student, even if you won’t understand everything included in it.

Update history:

Small modifications 22nd and 26th March 2025.

Small text modifications 7th April 2025.

Photo added 3rd May 2025.

Minor corrections and text modifications 27th June 2025.

Next steps and links added 19th October 2025.

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk