In this section you will find out about the research carried out by Ernest Rutherford and others to probe the internal structure of atoms. In a famous series of experiments they discovered that virtually all the mass of an atom is compressed into a miniscule nucleus and the rest… is empty space!

Background

Following Thomson’s discovery of the electron, scientists began trying to further investigate the internal structure of atoms. Working at Manchester University in the UK, Ernest Rutherford and his co-workers Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden studied the deflection of alpha particles by thin metal foils and sheets.

At the time of the experiments, the exact structure of alpha particles was unknown (the constituent particles had not be discovered) but they were known to be positively charged and have very high velocity and momentum. So, they reasoned that alpha particles might be influenced by any positive and negative charges inside the atom and hence be deflected from their original paths. They hoped that measuring such effects would allow the distribution of charge inside the atom to be deduced.

The work took several years, involved a number of different experiments and technical challenges. I have often heard a common misconception that the foils were only one atom thick; they were certainly extremely thin (around 0.00004 cm in some cases), but never-the-less, this is still hundreds / thousands of atoms thick given the absolutely tiny size of atoms.

How the Plum Pudding model would affect alpha particles

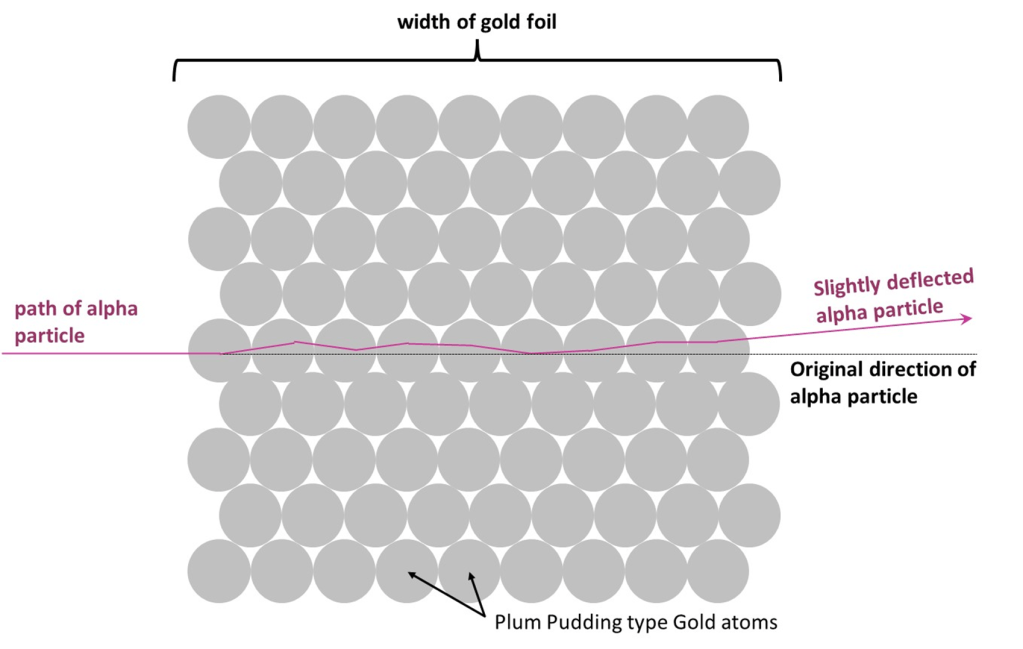

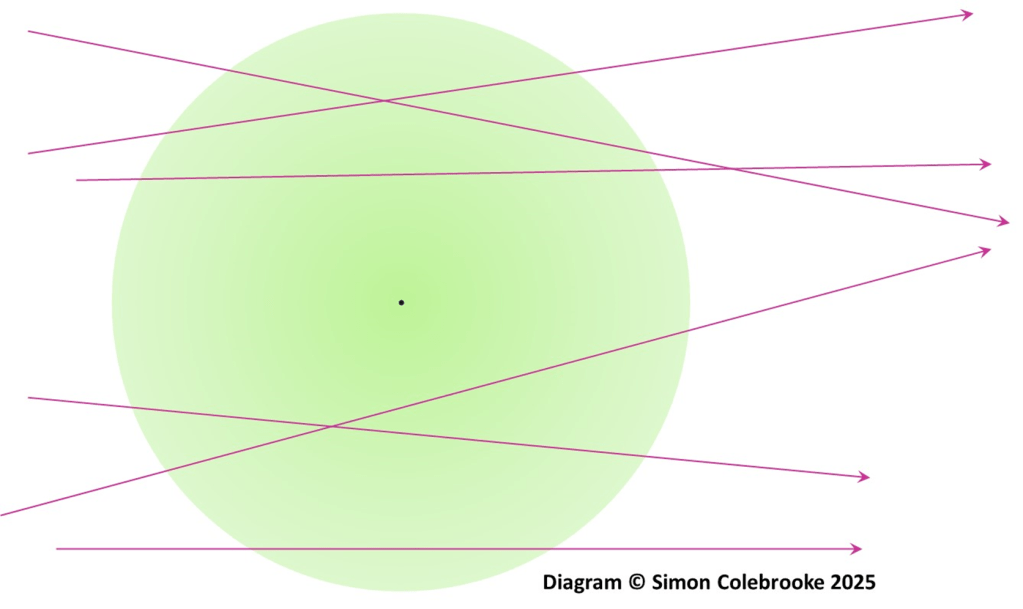

Thomson’s “Plum Pudding” was the mostly widely used model at the time and, in this model, the positive charge was spread throughout the entire atom (see notes section 1.2).

It was therefore expected that the alpha particles would only be deflected by small angles when passing through metal foils. The spread out nature of the positive charge within each atom would give rise to only small deflections and even though the alpha particles would pass through hundreds of atoms on their way through the foil, the cumulative effect would still be small.

I imagine it like this, where alpha particles are slightly deflected each time they pass through an atom, but sometimes a little bit one way, the next time a little bit the other… so overall, the final deflection on the other side of the foil is very small:

What was actually observed

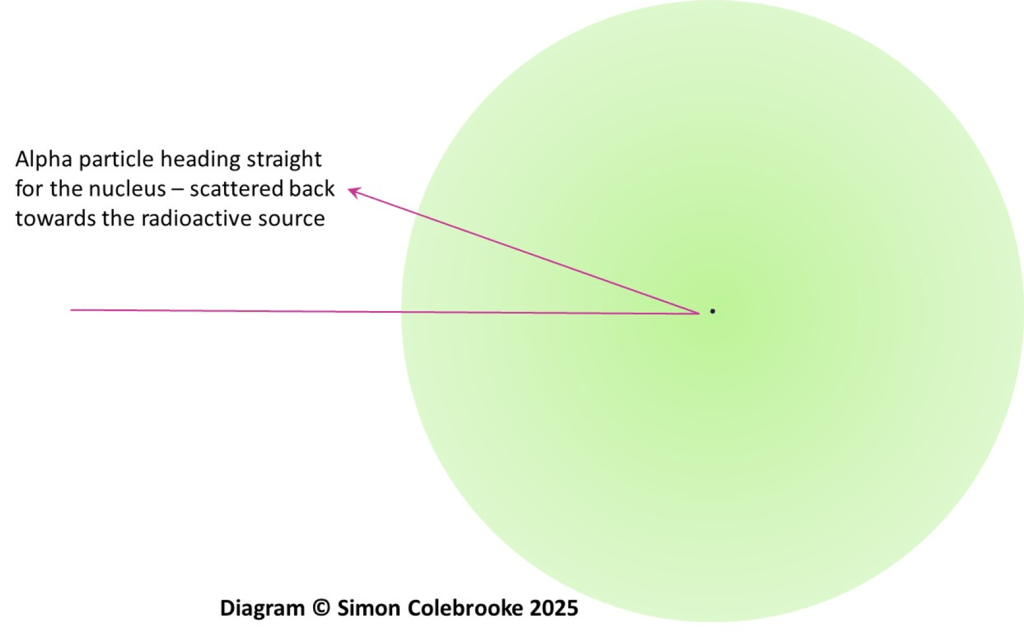

Small deflections were indeed observed for the vast majority of alpha particles. However, in 1909 Geiger and Marsden noticed that a small fraction of the alpha particles directed at gold foil (about 1 out of every 8000) were deflected by very large angles in excess of 90O . This observation was a complete surprise and led Rutherford to liken the effect to firing an artillery shell at tissue paper and finding the shell bounce straight back at you!

Attempting to explain these results, in 1911, Rutherford carried out some calculations to determine how likely it was that an alpha particle would undergo a large overall deflection by interacting with several atoms (one after another) as it travelled through the metal foil. He decided it was so unlikely that it was effectively impossible. Instead, he proposed that the large deflections arose from an alpha particle interacting with only one of the gold atoms it encountered on its’ way through the foil. However, for such large deflections to occur from one interaction only the atom must contain a region with very high electric field; all the atom’s positive charge must be concentrated in a tiny “nucleus” the diameter of which is much smaller than that of the gold atom overall. This was the end of the Plum Pudding model as it was inconsistent with these new experimental results. The negative charges (electrons) would then be spread somehow through the rest of the atom. Given that electrons were already known to be very much smaller than atoms, this meant – that remarkably – atoms were mostly empty space!

Many popular analogies exist for this startling revelation about atoms, for example;

A fly at the centre of the Albert Hall in London – with the fly representing the nucleus and the rest of the concert hall the empty space.

A pea at the centre of Wembley football stadium – where the pea is the nucleus and the emptiness of the atom is the space around the pitch and the stands.

Whichever analogy you choose, it’s a pretty incredible result!

Geiger and Marsden’s Experiment

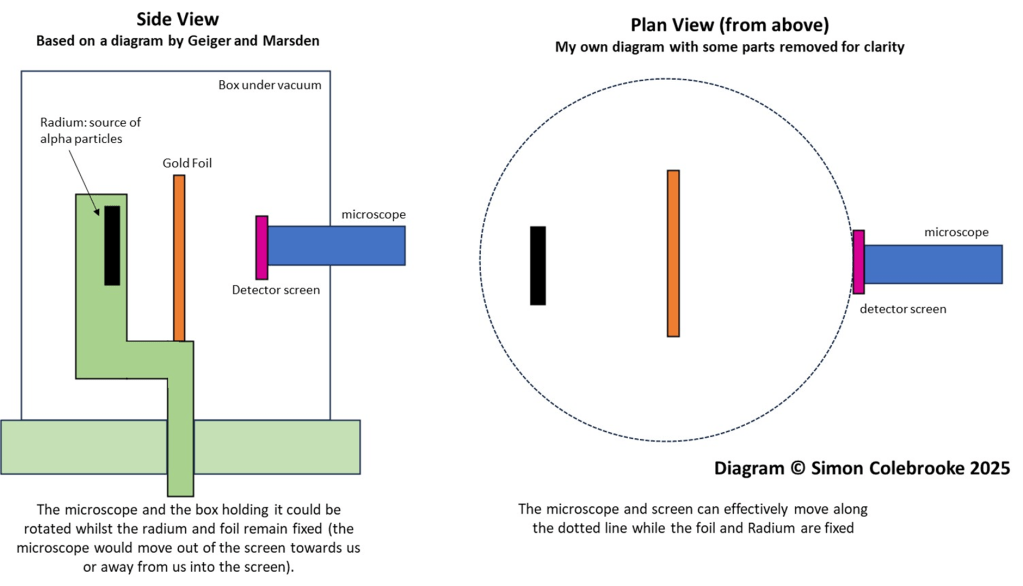

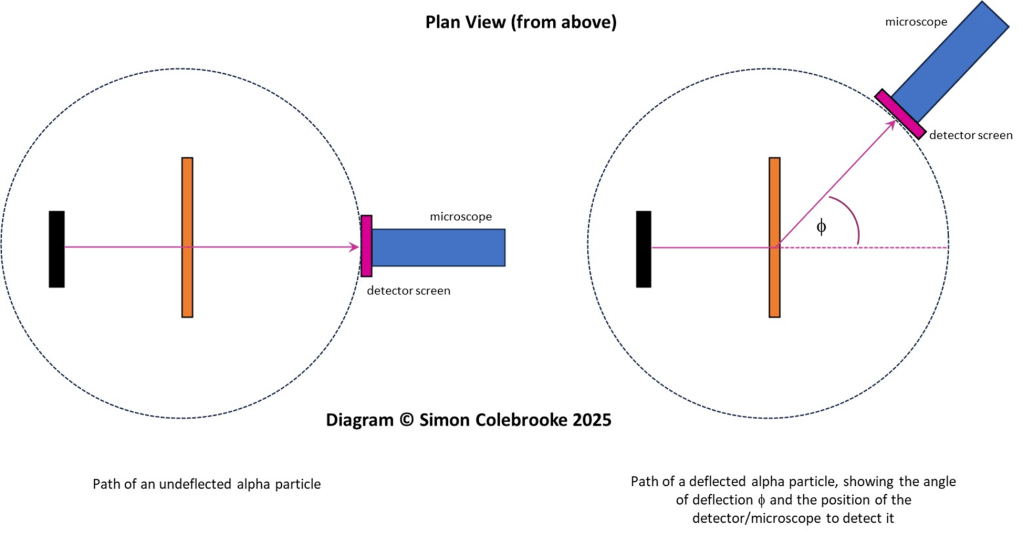

In 1913 Geiger and Marsden published a paper called “Laws of Deflection of alpha particles through large angles” in order to test the main points of Rutherford’s theory. They described several experiments where factors such as the metal elements used in the foil, the foil thickness, and type of radioactive source (hence alpha particle energy) were varied. Their results matched Rutherford’s theory extremely well. The setup shown in the diagram below is the most well known of their experiments.

The alpha particles were produced by a radioactive source, containing the element radium. In the experiment, alpha particles from this source were directed towards a thin sheet of gold foil. Geiger and Marsden would use a microscope to observe a screen made of zinc sulphide and count the flashes produced as it was struck by alpha particles. The angle between the screen and the original path of the alpha particles could be varied by rotating parts of the apparatus allowing the number of alpha particles detected at different positions to be measured. This was laborious work and took several weeks.

Due to restrictions in the size of the lead box containing the radium source, they were unable to measure deflections between 150 and 180 degrees.

The table shows some of the measured deflection angles with a thin gold foil taken from their paper in 1913:

| Angle of deflection / degrees | Number of “flashes” counted |

| 150 | 33 |

| 135 | 43 |

| 120 | 52 |

| 105 | 70 |

| 75 | 211 |

| 60 | 477 |

| 45 | 1,435 |

| 37.5 | 3,300 |

| 30 | 7,800 |

| 22.5 | 27,300 |

As the angle of deflection increases the number of observed flashes falls incredibly quickly – very few alpha particles were deflected by large angles and the majority passed through at angles below 22.5 degrees.

Additional measurements (see Table 2) were made for deflections at smaller angles, but needed a different radium source was required for this work, so the results do not correlate exactly as shown in Table 1. However, the same behaviour is clearly shown; most alpha particles underwent very small deflections.

| Angle of deflection / degrees | Number of “flashes” counted |

| 22.5 | 8 |

| 15 | 48 |

| 10 | 200 |

| 7.5 | 607 |

| 5 | 3320 |

Interpretation of results

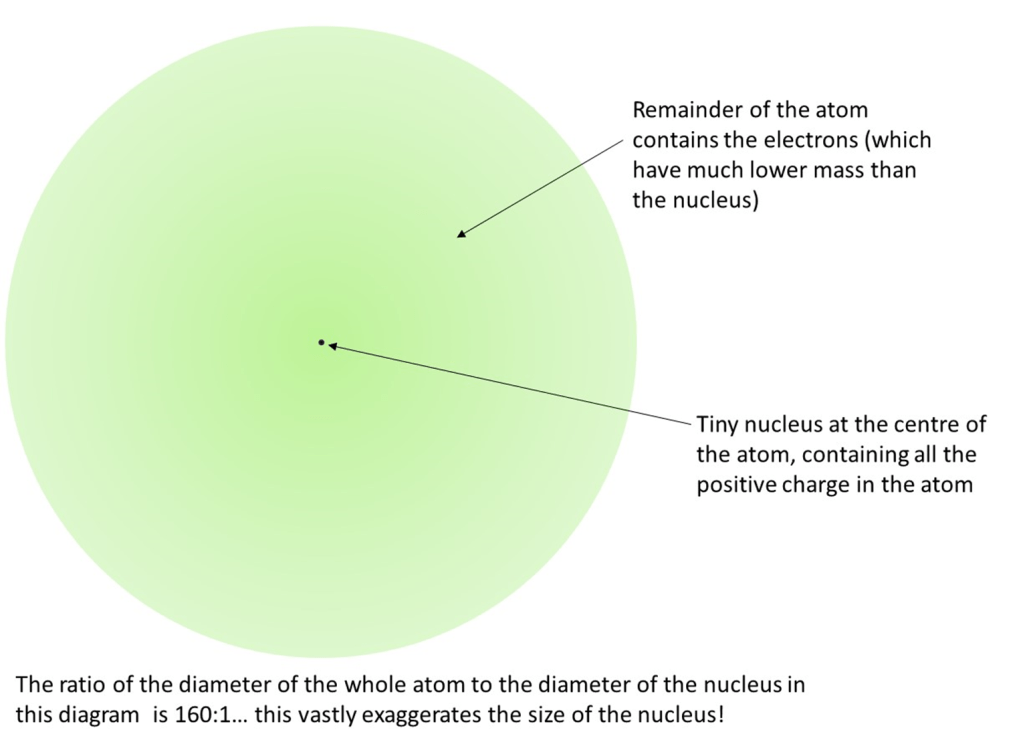

The observed large deflections and Rutherford’s calculations that these were caused by an alpha particle interacting with the positive charge inside a single atom forced a change to the model of the atom. Matter could not be made of atoms consisting of low density matter, spread throughout the whole atom as that would offer little resistance to alpha particles and not account for the extraordinary deflections observed in a tiny fraction of cases. Instead, atoms must contain a very dense, positively charged region, which would repel any alpha particles that passed in close proximity. Given that such a small fraction of alpha particles were deflected by a large angle, the dense positive region would have to be extremely small – this is the atomic nucleus. Rutherford’s estimate was that the positive charge was concentrated in a sphere with radius 3 x 10-12 m whereas the atom overall had a radius of 10-8 cm. In fact, the nucleus has to include virtually all the mass of an atom. The consequence of this is that the rest of the atom, outside the nucleus, is effectively empty, with the electrons arranged in that space somehow.

This “nuclear” model can be imagined as follows (although Rutherford did not produce a diagram like this himself).

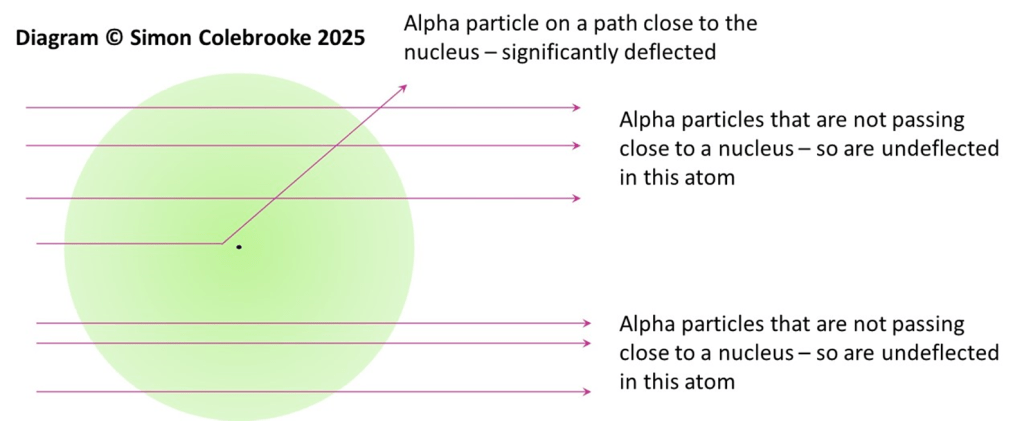

The model allows the alpha particle results to be interpreted as follows:

Alpha particles with small deflection: These alpha particles pass through only the mostly empty space within each gold atom they encounter in the foil. They never get close to a positive nucleus and are essentially unaffected by the positive charge. They pass through many gold atoms, but each time get nowhere near a nucleus.

Since an atom is mostly empty space, most of the alpha particles never get anywhere near a nucleus, and this accounts for the large numbers of alpha particles that go straight through the foil with minimum deflection.

Alpha particles with large deflection: Whilst passing through the gold foil an alpha particle happens to pass very close to one gold nucleus in one of the atoms. They are deflected by the intense positive charge of the nucleus and emerge from the foil having been significantly deflected. They may be unaffected on their passage through the empty space in every other gold atom, but this one interaction is enough to cause the observed large deflection.

In cases where the alpha particles happen to approach a gold nucleus almost head-on they are deflected right back towards the radioactive source.

Any summary of the experiments and calculations by Geiger, Marsden and Rutherford (like this one) are likely to be over-simplifications. For a start, this was not one experiment, but a whole series of experiments where the radioactive sources, type and thickness of foil and other parameters were varied. They had to contend with many complications and think about how to account for these. For example, the alpha particles would scatter off other parts of the equipment and interfere with the count, other types of radiation from the radium sources striking the screen, having to change the width of the alpha source for low angles, decreasing decay rates over time, the challenge of observing very fast count rates, and determining the number of atoms in foils of different thickness. Rutherford’s calculations include equations that will make even the most enthusiastic maths student puff out their cheeks and pull a few faces! Here is one that you can safely gloss over in A-level chemistry, but it makes the point that these discoveries were no easy task:

It is interesting to note that an additional conclusion by Rutherford was that the positive charges were about half the atomic weight; given the fact that electrons were known to have absolutely miniscule mass, this set the scene for subsequent discoveries in the next few years.

Clearly this research by Rutherford, Marsden and Geiger was a huge achievement. When you think about it enough, it will really change the way you view the objects around you.

What actually are alpha particles?

Alpha particles are now known to consist of two protons and two neutrons (no electrons). They are therefore the same as the nucleus of a helium atom and often represented as either:

or:

Geiger, Marsden and Rutherford didn’t know the exact structure of alpha particles as protons and neutrons were not known at the time. It is interesting that virtually all the helium on earth is formed from alpha decay of radioactive elements, which once emitted quickly interact with atoms in other substances to gain electrons to become helium atoms.

Suggested next pages

Think about the key ideas from this section about – try to summarise them as a set of bullet-points and click here to see if you’ve chosen the same as me.

You can follow these links to read more notes about protons or neutrons. You can select an icon below to return to the homepage, or try some questions about the nucleus or return to the notes menu.

“Copyright Simon Colebrooke 18th March 2025″

In writing this page I have referred to the following articles:

Geiger, H., and Marsden, E., On diffuse reflection of the alpha particles, Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 1909, 495-500.

Rutherford, E., The Scattering of a and b Particles by Matter and the Structure of the Atom, Philosophical Magazine, 1911, 6, 21.

Geiger, H., and Marsden, E., The Laws of Deflexion of a Particles through Large Angles, Philosophical Magazine, 1913, 25, 604.

Update History

Summary added 3rd November 2025.

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk