Following the nucleus, the next major development in determining the structure of atoms was the discovery of the proton. This had two main stages:

- The demonstration by Henry Moseley that the positive charge inside an atom was directly related to the atomic number

- A series of experiments by Ernest Rutherford to obtain protons from inside atoms.

Stage 1: The work of Henry Moseley

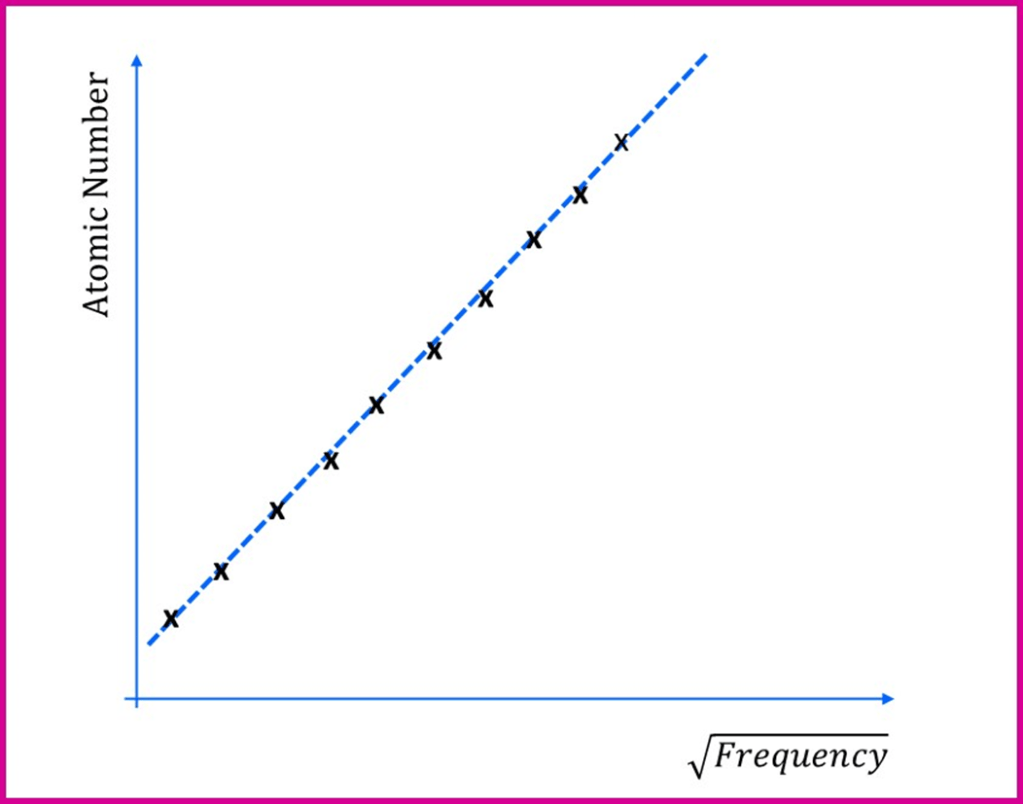

Henry Moseley worked in the same physics department as Ernest Rutherford at the University of Manchester. In 1913 he published a paper describing the results he obtained when a stream of high energy cathode rays (recently shown to be electrons by JJ Thomson) was directed at a range of different elements. Like other scientists had done shortly beforehand, he found that the elements emitted X-rays and he measured the frequencies of these X-rays as he varied the element and, hence, the atomic number. In 1913 he tried this for the 11 elements from calcium to zinc and in 1914 extended this further to around 40 elements in total. He found that when the atomic number of the element was plotted against the square root of the frequency he obtained a straight line, something like this simplified version below:

In other words, the square root of the frequency was proportional to the atomic number. This might not seem like all that big a deal… but at the time, the atomic number was just a “label” showing the position of an element in the periodic table when the elements were arranged by mass. Many scientists thought the mass was the really important feature of an atom. However, Moseley’s results showed the atomic number actually meant something about the structure of the atom. It wasn’t just a label, because the actual behaviour of the atoms depended upon it very precisely. The atomic number was related to a measurable physical property of atoms.

From these results Moseley made a number of conclusions:

i) There is a fundamental quantity in an atom that increases by regular steps from one element to the next, in the atomic number sequence.

ii) That quantity can only be the positive charge on the nucleus, which was already known to be roughly half the atomic weight.

iii) To get a linear graph, the positive charge must increase by a fixed unit for every increase in atomic number.

iv) The number of positive charges in an atom must be the same as the place (atomic number) of the element in the periodic table.

v). The chemical properties of elements will be determined by the number of positive charges and not the mass (and working out what the mass of an element will be must be more complicated).

vi) It is therefore the atomic number that defines the element and not the atomic weight, as previously believed.

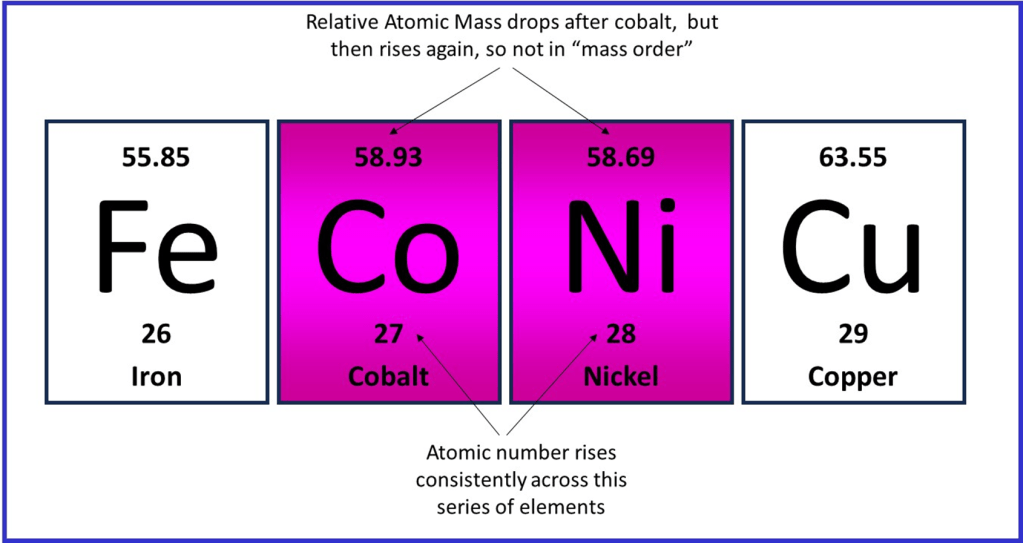

Interestingly, this development in understanding about atoms neatly resolved a discrepancy in the ordering of elements in the periodic table. For sometime cobalt and nickel had been placed out of atomic mass order, so as to keep the chemical properties well matched; cobalt had a slightly higher atomic mass than nickel. However, once atomic number was known to be the key feature of an atom by which they should be ordered, cobalt should come before nickel based on the X-ray frequency emitted.

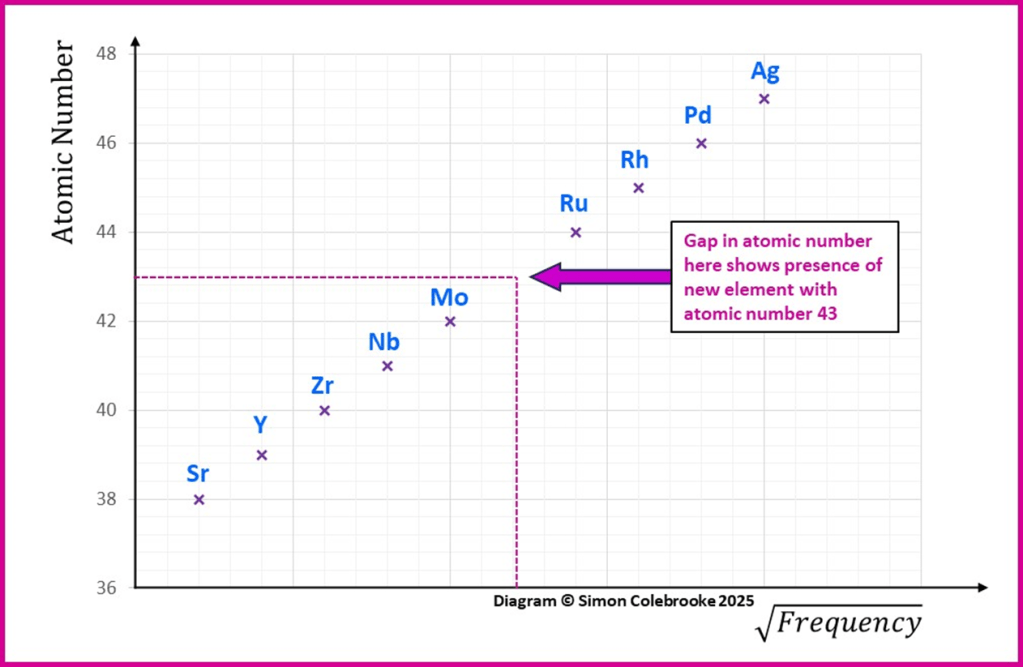

Moseley even predicted that new elements could be discovered using his analysis method. Based on the X-ray frequency and hence nuclear charge there appeared to be elements missing, so he proposed attempts could be made to find these elements. I have illustrated the idea on the graph below, where the square root of the frequency increases in regular steps, but where a gap occurs towards the centre of this plot a point representing an unknown element ought to be. The diagram shows the kind of data that would indicate an element at atomic number 43 ought to be present between molybdenum and ruthenium. This element was discovered in 1947 and is now known as technetium, the frequency of emitted X-rays matches that proposed by Moseley.

Stage 2: Rutherford finds the proton

A few year’s later Rutherford began to investigate what happened when different elements were exposed to alpha particles. In one particular experiment he looked at the effect of alpha particles on a sample of nitrogen. Alpha particles were emitted from a radioactive source inside a box containing nitrogen gas and any particles produced in the resulting collisions could exit the box via a hole at one end. However, the hole was covered with a silver plate, thick enough to prevent any alpha particles coming through. Beyond the silver plate was a zinc sulphide screen that would flash when struck by particles from inside the box and the set-up is shown below:

The intriguing result was that the screen detected particles whose properties matched hydrogen and not nitrogen! And Rutherford had been careful to ensure there was no hydrogen inside the box. Rutherford’s conclusion was that the hydrogen had come from inside the nitrogen atoms; in other words, he had somehow broken apart the nucleus of some nitrogen atoms, causing hydrogen nuclei to be produced. The hydrogen nucleus is in fact just a single proton and Rutherford was able to measure the properties of these hydrogen nuclei to confirm that.

Rutherford thought of the alpha particles rather like projectiles and imagined them creating intense forces on the nitrogen nuclei, if they happened to get close to one. He was not surprised that the nitrogen broke apart or “disintegrated” to use his own phrase, because of the incredible forces he imagined such a collision would cause. In the process, the nitrogen atoms became oxygen atoms, which I will write more about in the nuclear reactions section. This famous experiment is now referred to as Rutherford “splitting the atom”.

So Moseley found the positive charge increased by one fixed unit for each increase in atomic number and Rutherford found that positive charges equivalent to hydrogen nucleus, with an atomic number of 1, were obtained from other elements. This is effectively the proton, and we now know that every successive element has one more proton than the previous one. The word itself was first used by Rutherford meaning “first” as most atoms of the first element hydrogen have a nucleus with only one proton.

What are protons made of?

In the 100+ years since the discovery of the proton, scientists have determined that protons are not actually “fundamental” particles because they are also made of other things. Specifically, they are made of three mysterious sounding particles called quarks (2 “up” quarks and 1 “down” quark, which sounds even more bizarre). However, this is entering the realm of particle physics and not really chemistry anymore… so we won’t go into that any further now.

By contrast, electrons do seem to be fundamental particles and not made out of even smaller stuff.

What happened to Moseley?

Moseley was only in his early 20s when he carried out the research relating the atomic number to the nuclear charge. Unfortunately, very soon afterwards his life came to a tragic end. When the first world war began in 1914 Moseley enthusiastically enlisted into the army and soon ended up working in communications and signalling. In 1915 he was killed in Gallipoli in Turkey aged only 27. Who knows what he could have achieved if he had spent a full life in scientific research.

Rutherford campaigned to prevent leading scientists going to the frontline and later in the war they were allowed to carry out research towards military aims instead.

Let’s hope that we get to a point in the future where no one (scientist or not) has to go to a frontline and get shot.

Copyright Simon Colebrooke 17th May 2025.

Suggested next pages

In writing this article I have referred to the following articles:

The high frequency spectra of the elements. Moseley HGJ, Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 1913, 1024-1034.

Collision of alpha particles with light atoms. IV. An anomalous effect in Nitrogen, Rutherford, E., 1919, Philosophical Magazine Series 6, 37:222, 581-587.

Update History

Diagrams added 19th-21st May 2025.

Text modifications 21st May 2025.

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk