Background

After the discovery of the proton, scientists continued experiments to find out more about the internal structure of atoms. Although it was known that most of an atoms’ mass was contained in the nucleus and that positive charges were present there, the exact construction of this nucleus remained unclear. There were also some discrepancies involving mass measurements, whereby the mass of the positive charges did not fully account for the whole mass of the atom – remember, electrons were known to have miniscule mass compared to nuclei. So, scientists did not know whether a) the nucleus contained additional positive particles, the extra charge of which was cancelled out by some electrons in the nucleus, or, b) there was another type of particle present, which had no charge but contributed to the mass.

In 1932, James Chadwick (working in Cambridge) gathered the evidence to answer this question. He followed up recent research by other scientists who had directed alpha particles produced by polonium at pieces of beryllium, causing some additional radiation to be released. This radiation was not easily detected, although some thought that it could be in the form of gamma radiation . Irene Curie (daughter of Marie Curie) and others had found that this additional radiation was capable of pushing protons out of a sample of paraffin wax which was put into it’s path and these could be detected via their ionising effect in a small chamber of gas.

Chadwick’s experiment

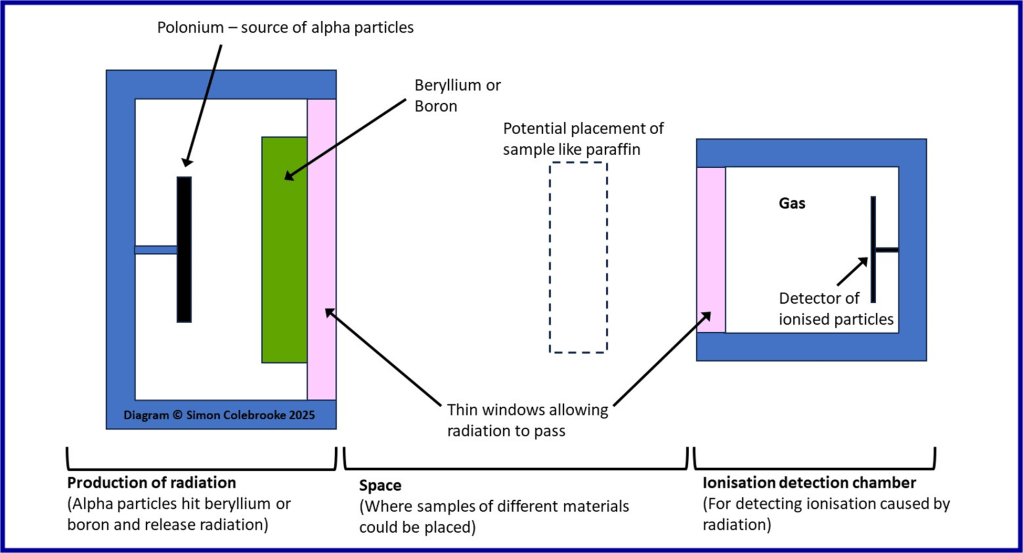

Chadwick repeated and extended these experiments, making numerous careful measurements. His experimental setup was relatively complex and here is a diagram labelling the parts as I understand it:

Here is how the experiment with paraffin wax worked:

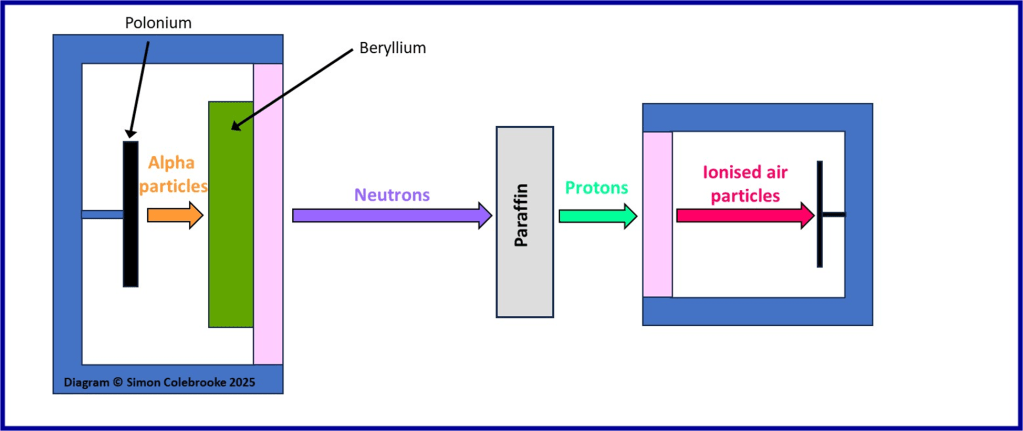

i) High energy alpha particles were released from the polonium source

ii) These alpha particles interacted with nuclei in the beryllium, with excess energy being emitted as some form of radiation.

iii) The radiation produced in step ii) could not be deflected or easily detected, but when it hit a paraffin sample placed in its’ path – as shown by the dotted outline in the diagram – protons were emitted from the paraffin.

iv) The positively charged protons travel into the detection chamber and ionise gas molecules (which means they take electrons from them creating charged particles or “ions”).

v). The ionised gas molecules were then detected by creation of an electric current.

By measuring the number of ionisations that occurred and the energy of the ionised gas molecules Chadwick could calculate what the energy of the protons must have been and, from that, he could work out the energy of the radiation coming from beryllium.

Chadwick discovered that Curie’s result – finding protons emitted from a paraffin sample – was more generalised. He could get similar effects to occur when other material types were used, measuring ionisations with hydrogen, helium, air, carbon and lithium in place of paraffin.

Chadwick also found that the beryllium radiation was extremely penetrating – it would travel quite long distances through air or even through sheets of metal. This implied it didn’t have an electric charge, otherwise it would have interacted more strongly with atoms in the air or metal and not travelled so far.

What Chadwick concluded from the measurements

By considering the amount of energy involved with the various processes involved in this experiment, and the large amount of ionisation caused in the detection chamber, Chadwick decided that the radiation produced from the beryllium sample could not be electromagnetic radiation like gamma rays. Radiation of that type would need to have incredibly high energy to remove protons from paraffin and even higher energy to knock larger particles from the other samples he used.

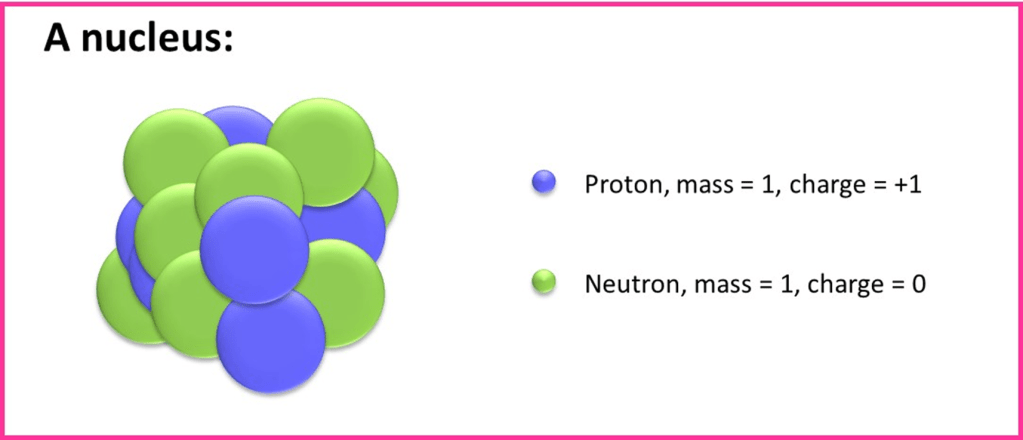

Instead, he concluded that the measurements were consistent with particles being emitted from beryllium, if the particles had neutral charge and mass very similar – or just above – that of a proton. Chadwick therefore proposed that the radiation emitted by beryllium was in the form “neutrons” with relative mass 1 (a proton would have the same value) and zero charge. His calculations actually estimated the mass of a neutron to be between 1.006 and 1.008 times that of a proton – in other words, marginally more massive.

The diagram below summarise Chadwick’s proposal in terms of the types of particle and radiation present at each stage of an experiment with a paraffin sheet inserted:

Significance of neutrons

The discovery of the neutron was a major step forward. Chadwick realised immediately that neutrons were going to be present in the nuclei of almost all atoms. Indeed, he had been able to produce them from samples of more than one element and they had been proposed to take part in some nuclear reactions and decay processes. The properties of the neutron were soon used to develop nuclear physics, nuclear energy and the generation of completely new elements via nuclear reactions. The work was significant enough for Chadwick to win the Nobel prize for Physics in 1935.

It is interesting to note that Chadwick initially suggested that neutrons were made from a combination of a proton and electron in close association. This would explain the neutral charge and the slightly higher mass of neutrons compared to protons. On this point Chadwick was mistaken and in the 1960s scientists found that neutrons are actually made from quarks, so that now, we understand that nuclei contain only of protons and neutrons:

“Copyright Simon Colebrooke 18th June 2025″

In writing this article I have referred to these two publications by James Chadwick in the early 1930s.

Possible Existence of a Neutron, J. Chadwick, Nature, 1932, 129, 312.

The Existence of a Neutron, J. Chadwick, Proceedings of the Royal Society A, Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences, 1932, 136, 830, 692-708.

Suggested next pages

Click the icons below to either return to the homepage, or try a set of questions on this topic (choose the Q icon) or return to the notes menu (N icon).

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk