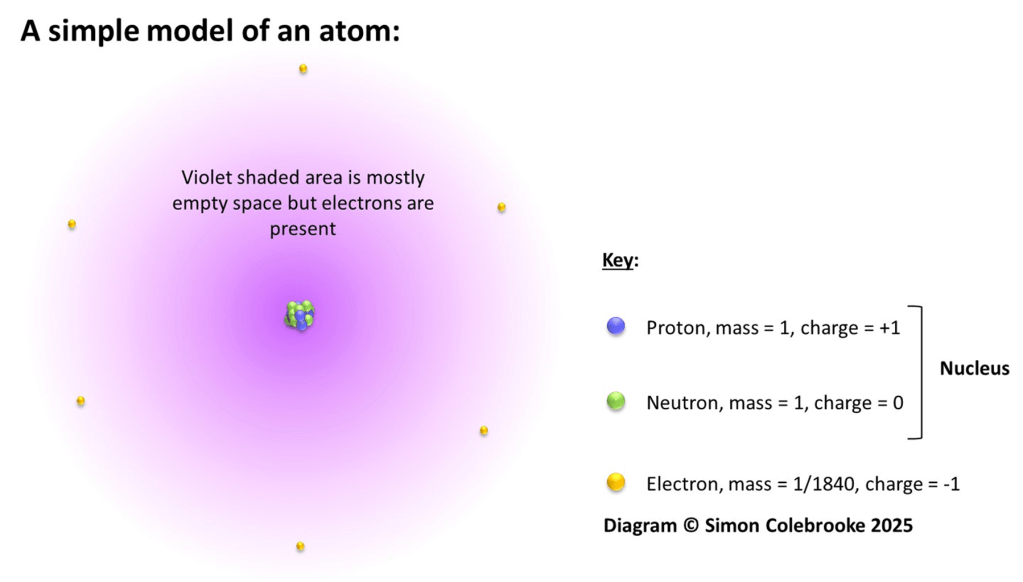

We can now use the atomic models and discoveries of scientists like Thomson, Rutherford and Chadwick (see sections 1.1-1.6) to determine how many protons, neutrons and electrons – the “sub-atomic” particles are in any atom or ion. The simplistic diagram below summarises some of the key information:

Diagram 1: A simple model of an atom showing the relative locations of protons, neutrons and electrons. Remember that in this diagram, the size of the nucleus is hugely exaggerated !

Mass and charge are two important properties of these three subatomic particle and are listed in Table 1:

Table 1: A comparison of the mass and charge of protons, neutrons and electrons.

The values for the actual mass and charge are incredibly small and rather awkward to use. Hence, it is common to refer to their “Relative Mass” and “Relative Charge” which allow an easier comparison.

In terms of mass, both protons and neutrons have a relative mass of 1 which means their actual masses are the same (Table 1 shows that actually neutrons are marginally heavier, but the difference is so tiny it is negligible for chemistry). Electrons are much lighter, almost 2000 electrons are needed to give the same mass as 1 proton or neutron.

Only protons and electrons have electric charge and these are equal in size (measured in a unit of charge called Coulombs) but opposite in sign; protons being positive and electrons negative. They therefore have relative charges of +1 for the proton and -1 for the electron.

Nuclear symbols

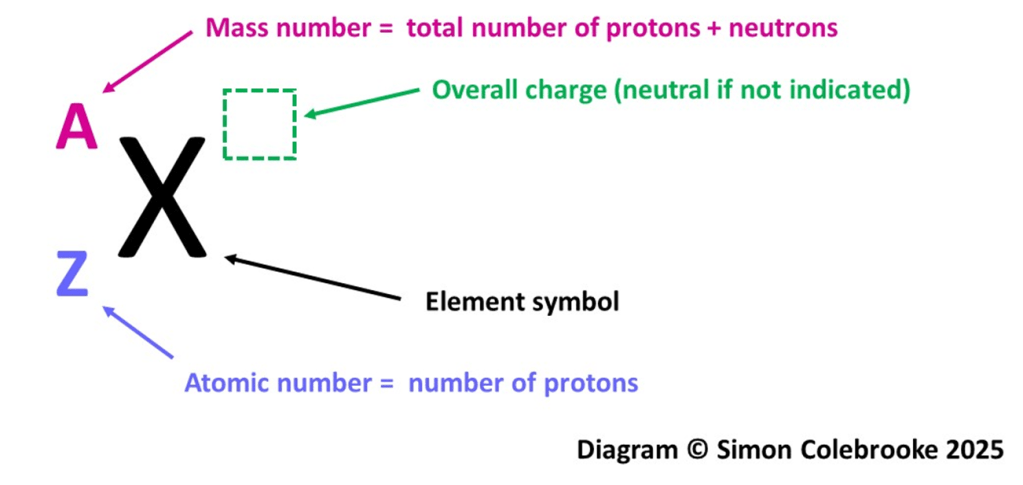

Information concerning the composition of atoms and ions (sometimes loosely referred to as “species”) is frequently given using a “nuclear symbol” as shown in Diagram 2.

Diagram 2: The location and meaning of numbers in a nuclear symbol.

The element is shown using the familiar symbols from the periodic table with two numbers as a subscript and superscript (to the left of the element symbol). The value at the bottom left is the atomic number and the value at the top left is the mass number. Note that this may well be different to the display used on a periodic table – different reproductions can change the location of the atomic number for stylistic reasons. The nuclear symbol however, should always be presented as shown in the figure above.

Atomic Number / Proton Number (Z)

This is the value that defines the element and is equal to the number of protons in the nucleus. The element symbol must always match this atomic number. Two atoms or ions with the same atomic number are the same element.

Mass Number

Table 1 above shows that only protons and neutrons contribute significantly to the mass of atoms; the electron mass is so tiny that it can usually be ignored in chemistry. Hence the mass number is the total number of protons and neutrons in an atom or ion.

However, this is a “relative mass” number, not the actually mass in kg, but effectively the mass of the atom or ion compared to a single proton (or neutron) which have a relative mass of 1.

Number of neutrons

Since only protons and neutrons contribute significantly to the mass, the number of neutrons can be found by a simple subtraction involving values in the nuclear symbol:

No. neutrons = (Total no. protons + neutrons) – (No. protons)

No. neutrons = A – Z

The number neutrons is thus the difference between the mass number and the atomic number.

Number of electrons

The number of electrons is not directly indicated by either of the numbers in a nuclear symbol, but can be easily determined by considering the charge, which will be indicated in the top right hand corner if it isn’t zero.

If there is no charge indicated, the species under consideration is an atom, with equal number of protons and electrons. The reason these must be equal is evident from Table 1; only protons and electrons have charge and their charges are equal and opposite. Hence, if the number of protons and electrons is the same, there is no charge overall, the positive charge of the protons is exactly cancelled by the negative charge of the electrons.

On the other hand, if the species is an ion and has an overall charge then the number of protons and electrons must be different.

A positive ion has more protons than electrons; the total positive charge of the protons is not completely cancelled by the negative charge of the electrons. The number of excess protons is shown by the size of the positive charge.

A negative ion has more electrons than protons; the total negative charge of the electrons is not completely balanced by the positive charge of the protons. The number of excess electrons is shown by the size of the negative charge.

A number of examples will illustrate these points:

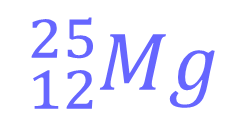

Example 1

The atomic number is 12, hence there are 12 protons. Note that the element is magnesium, since that is the element with atomic number 12.

Since there is no overall charge, this is a neutral atom and the number of electrons must also be 12.

The mass number (protons and neutrons) is 25. Since we already know that there are 12 protons, the number of neutrons must be 25-12 = 13.

Example 2

This species also has the atomic number 12 (hence 12 protons) and a mass number of 25 (hence 25-12 = 13 neutrons). However, there is now an overall 2+ charge. This is a positive ion and so the number of protons must exceed by two, the number of electrons. Since we already know there are 12 protons, there must be 10 electrons.

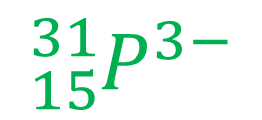

Example 3

This is a negative ion of phosphorus (correct name is phosphide). There are 15 protons, indicated by the atomic number and the use of element symbol P. The number of neutrons is therefore 16, since the total mass is 31. The negative charge indicates there are 3 more electrons than protons, which is 18 electrons in total.

Example 4

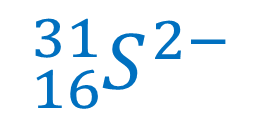

Sometimes, doing this process in reverse helps to consolidate the ideas. What would be the nuclear symbol for a species with 16 protons, 15 neutrons and 18 electrons?

The number of protons decides the element; 16 protons means sulfur. We therefore know the element symbol to use (S) and the atomic number. The mass number is the sum of the neutrons and protons; in this instance, 16 + 15 = 31. Finally, we need to decide if there is a charge. The number of electrons exceeds the number of protons by 2; hence there will be a negative charge of 2- as the negative charge of the electrons will exceed the positive proton charge. Hence this is a sulphide ion and the nuclear symbol of this species will be:

Isotopes

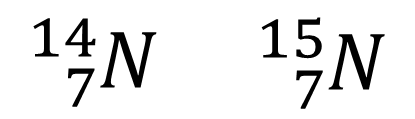

An element is defined by the number of protons. This means that it is possible to vary the number of neutrons or electrons without altering the element. Consider the two nuclear symbols below:

Both these species have 7 protons, so both are atoms of nitrogen. The species with mass number 14 must have 7 neutrons, whereas the species with mass number 15 has 8 neutrons. Neither has an overall charge, so both are neutral atoms.

These two species are called “isotopes”; they are atoms of the same element with the same atomic number, but different masses due to the difference in the number of neutrons.

It turns out that the vast majority of nitrogen atoms are the type with mass of 14; over 99.5% of all the atoms. Only about 0.3% have a mass of 15. However, this does not mean there is a “correct” isotope as many students often state, but just that there are two naturally occurring isotopes and most are of the mass 14 type. I suspect this wording error comes from the fact that the mass for nitrogen quoted on most periodic tables is 14.0, which is obviously closer to 14. However, that reflects the fact that the 14.0 on a periodic table display is a “Relative Atomic Mass” (see section 2.1) and is an average mass of all the nitrogen isotopes.

Common notation

A common way of discussing different isotopes is to write the element name and then the mass. In this notation the two isotopes described above would then be:

nitrogen-14

and

nitrogen-15.

Note that the number must indicate the mass – the atomic number of both isotopes has to be 7 as they are both the element nitrogen.

Difference to periodic table

It is very important to recognise the differences between one of these nuclear symbols and the information displayed on the periodic table. There are two key points:

1). The nuclear symbol follows a conventional layout; the atomic number is always displayed at the bottom and the mass number at the top, and both these values are located to the left of the element symbol. By contrast, the information inside each of the cells on a periodic table varies (according to design preferences) from one periodic table to the next. Sometimes the atomic number is the bottom number in the cell, but sometimes it is to the top and sometimes elsewhere. You should always refer to the “Key” assuming there is one, which indicates the arrangement chosen for that particular periodic table.

2. A second and conceptually more important feature involves the mass number. In a nuclear symbol the mass number is the mass of a specific atom or ion in mass units and – since it is the sum of the protons and neutrons – it must always be an integer (whole number), as it is not possible to have “parts” of a proton or neutron. The number relating to mass in each cell of a periodic table is actually the “Relative Atomic Mass” (RAM), which is a weighted average including all the isotopes of an element. This is more fully defined in Section 2. It is not an integer and it doesn’t have any meaning for a single atom or ion; it is an average and so only applies to a sample of many atoms. The relative atomic mass is therefore a “bulk” quantity compared to the “sub-microscopic” quantity of the mass number for one atom or ion.

We need to use the mass number of a specific atom or ion when determining the number of protons, neutrons and electrons in a given species and should never use the relative atomic mass for this; the RAM is an average and different isotopes of the same element differ in the number of neutrons.

We should however, always use the RAM when weighing out a real life sample of a substance – the number of individual atoms or ions in the sample will be so vast that we expect all the possible isotopes to be present according to their natural abundance. Hence, we should not round the RAM value to get a whole number, or it will no longer reflect the contribution of all the isotopes.

Questions

Having completed reading this section, try a set of questions to test your understanding:

Question set 1.7 on The number of protons, neutrons and electrons in atoms and ions

Suggested next pages

Links to appear here for suitable next pages to read.

“Copyright Simon Colebrooke 19th March 2025″

Update History:

Minor text changes on 26th March 2025.

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk