Different models for arranging electrons

At GCSE level chemistry, students are introduced to the idea that there is a pattern in how electrons are arranged in atoms. The model used at that stage of education is one of electrons arranged in shells, with each shell containing a certain number of electrons, up to some maximum value. Different shells are able to contain different numbers of electrons and each shell is further away from the nucleus than the previous one. This type of model is represented in diagrams like the one below, with each dotted line showing one shell. It is a simple model, which works well for introducing students to topics like covalent and ionic bonding but it doesn’t completely represent everything that chemists know about electrons.

Consequently, the model shown above is not complex enough to explain everything that you need to understand at A-Level and so a new / more sophisticated one is needed. Describing this model is the aim of this section of notes. However, it is important to point out two things:

1). The GCSE model is not “wrong” as such, it is just simplified enough that students can begin to learn some basic ideas. It conveys many of the key ideas and several of it’s features will still appear in the A-Level model.

2). The A-Level model will not tell us everything chemists know about electrons either and is not sufficient to explain some more advanced phenomena. However, it will allow you to make more progress and understand many aspects of chemistry more fully. If you go on to study chemistry at university you’ll meet other even more sophisticated models…. but that is how studying science is supposed to be; you can’t go straight to the most complex ideas, you have to build up to them gradually.

Properties of electrons

Before introducing the new model it is helpful to summarise what is known about electrons:

They have negative charge (with relative value of -1).

- An electron mass is only about 1/1840th that of a proton, which is such a small contribution to the total mass of an atom that it can usually be ignored.

- Electrons occupy the space around the nucleus (which accounts for the vast majority of the space in an atom).

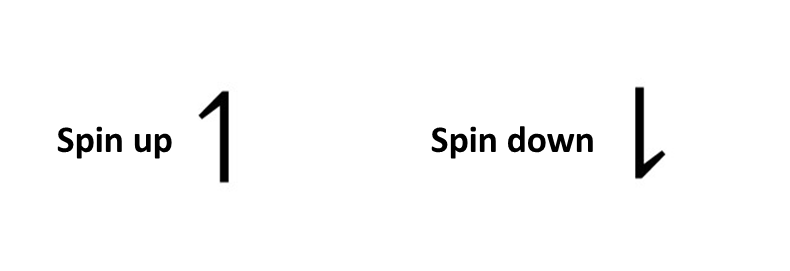

- Electrons also have another property called “spin”. It is not really spinning in the way that a ball can spin on an axis, although it doesn’t matter if you visualise it that way. Spin is just a label for the two different states an electron can be in; either “spin-up” or “spin-down”.

These two spin states are usually represented with half arrows:

Arrangement of electrons

By studying properties of atoms such as ionisation energy and emission spectra and theoretical modelling, scientists have concluded a number of things about the arrangement of electrons in atoms:

1. Orbitals

Electrons are arranged in regions of space called “orbitals”. These are not in the form of “rings” as often seen in models of atomic structure studied in the early years of secondary education, but rather they are 3D regions of space where there is a high probability of electrons. I have written a separate page of notes about the shapes of orbitals to try and help you understand this aspect of electron arrangement (link to appear to Section 1.10). The orbitals always have the nucleus at the centre.

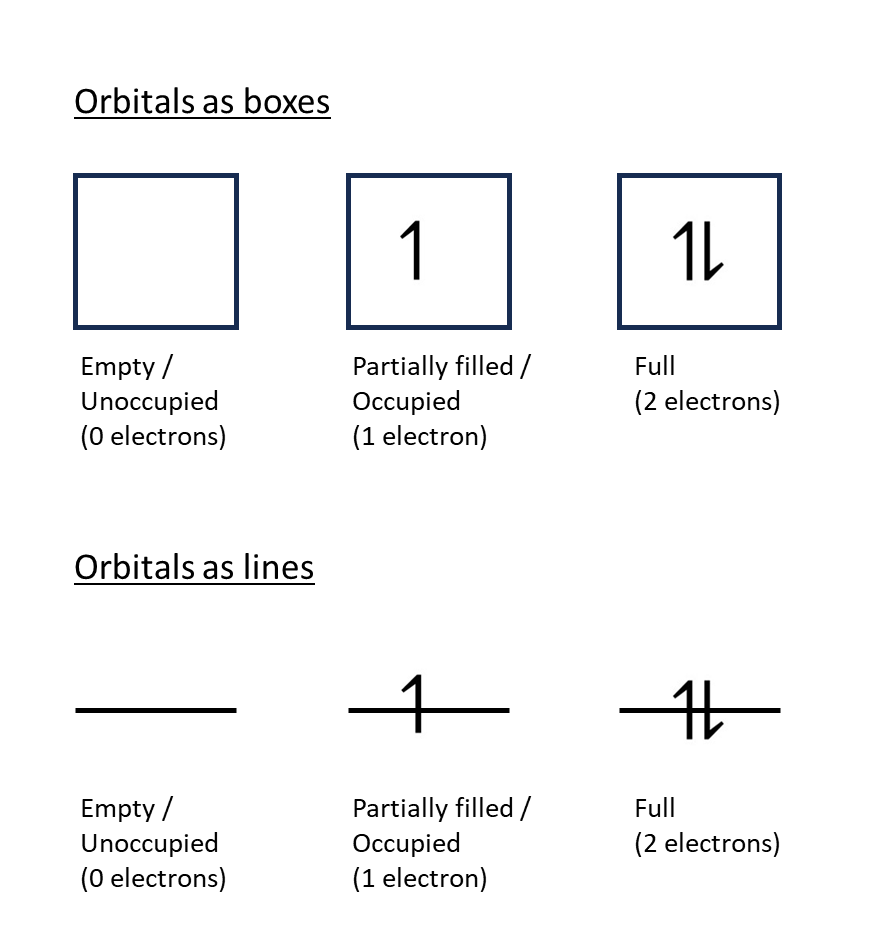

Orbitals can be:

a) Empty: when there are no electrons in the orbital

b) Partially occupied: when there is one electron in the orbital

c) Full: when the orbital contains two electrons with opposite spins (i.e. one spin-up and one spin-down)

Common representations of orbitals in diagrams are as either boxes into which the electrons are placed, or lines onto which electrons are drawn. These two representations and the three states a)-c) are shown below:

Orbitals can never contain two electrons with the same spin.

2. Different orbital shapes

The regions of space representing each orbital can vary in size, shape and orientation, but they are always centred on the nucleus. The basic shapes are indicated with a single lower-case letter and the common shapes you will need to know for A-level are:

s-orbitals, based on spheres with the nucleus at the centre

p-ortbials, dumb-bell / infinity symbol shapes, with the nucleus at the centre

d-orbitals, more complex shapes, reminiscent of flower petals (plus one resembling a doughnut around a p-orbital!)

The letters used in this spd notation are actually derived from features of lines observed in atomic emission spectra, rather than the orbital shapes themselves.

3. Sub-shells

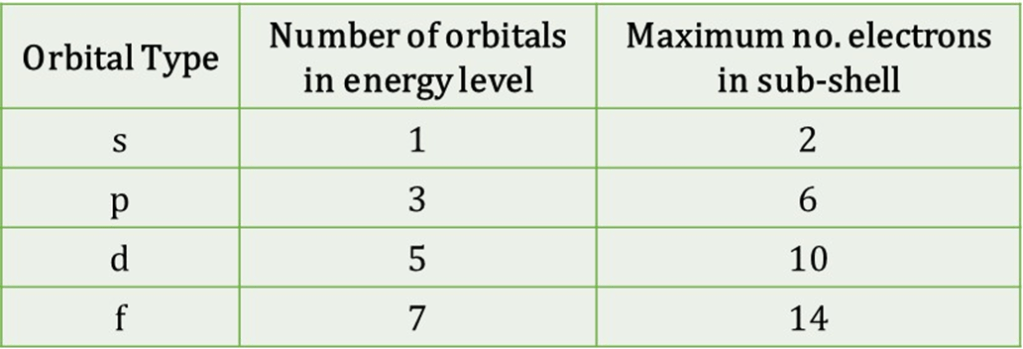

Orbitals of one type are then grouped together into “sub-shells” with each orbital in the sub-shell having the same energy. Sub-shells are therefore often called “energy levels”. The number of orbitals within each sub-shell are given in the table:

The organisation of orbitals into different energy level subshells is show in the figure below, with the energy of the subshell increasing higher in the diagram.

You will need to learn this sequence of energy levels. However, there are some patterns that will help.

First, each shell (shown as different colour orbitals on the diagram above) repeats everything from the previous shell, but adds an additional sub-shell.

Second, each type of subshell contains the same number of orbitals; p-subshells always contain 3 orbitals, whereas s-subshells only consist of a single orbital. This is due to the symmetry of the orbital type. You can envisage that there is only one possible orientation of a spherical orbital around the nucleus, but three equivalents arrangements for p-orbitals, along the x, y and z axes.

A third pattern is that each shell repeats all of the subshell and orbital arrangements of the previous shell, but adds on new subshell at higher energy. The number of orbitals in a subshell increases by two from s (1 orbital) to p (3 orbitals) to d (5 orbitals) to f (7 orbitals) and so on.

A-Level courses are unlikely to require a full electron configuration of any atom or ion filling beyond 4p. However, it is relatively easy to be able to give the arrangement of electrons in the highest occupied shell, for any element in the s- p- or d-blocks of the periodic table.

It is common for students to confuse “subshells” and “orbitals”. The difference will be highlighted in examples 1-4 below.

Total electrons in a shell

Sub-shells are then grouped together into shells.

Given that each electron orbital can hold a maximum of 2 electrons, the maximum number of electrons which each shell can accommodate is calculated in the table below:

The shells are then numbered from 1 upwards, with a value “n” called the “Principal Quantum Number”.The maximum number of electrons which can fit into each shell is then equal to 2n2, where n is the shell number.

Rules for filling orbitals with electrons.

Three relatively simple rules can be used to determine how electrons will fill the energy levels in an atom:

- Aufbau Principle: Energy levels fill with electrons in order of increasing energy. One energy level must be completely filled before the next energy level begins.

- Pauli Principle: Orbitals can hold a maximum of two electrons and only if the electrons have opposite spins (one is spin-up, the other spin-down)

- Hund’s Rule: If a sub-shell contains more than one orbital, the orbitals in that sub-shell fill up with one electron each, before any of the orbitals fill with a second electron. Electrons in singly occupied orbitals at the same energy level always have the same spin.

Electron filling analogy

It can be helpful to consider the following analogy when filling up the energy levels of an atom. I do not know who devised this analogy originally, but I have found it very useful over the years – so if by some miracle they are reading this website – thank you!

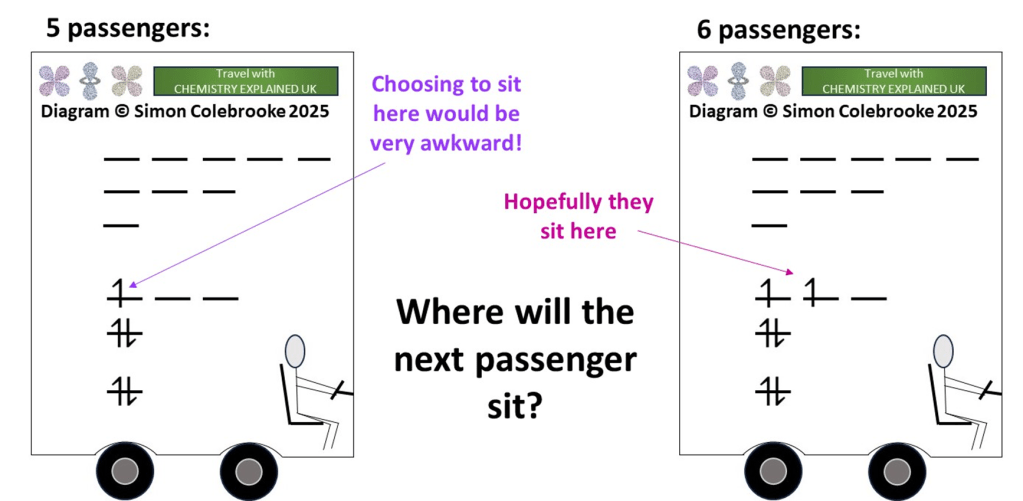

The idea is to imagine the electron energy levels as the floors of a very tall multi-storey bus. The orbitals are the kind a double seats you often get on busses that can fit two passengers, side by side. The electrons are the passengers.

Here, on the left, is the bus as it approaches the next stop:

Because it takes a lot of energy to climb the stairs to the higher levels, the passengers already on board (electrons) have chosen to sit on the lowest decks first. Only when no seats were available on a given level, did they climb more stairs to the next one. This represents the Aufbau Principle.

Currently five passengers are on board and there is one sitting alone on the third level. As the bus arrives at the next stop where will the new passenger choose to sit? They will have to go up to the third level because all the others are filled, but when they get there they can either a) join the lone passenger directly next to them in the double-seat or b) take a new double-seat all to themselves.

If you travel by public transport to school / college you will know that real passengers with always choose option b)! If you were alone on a bus and a stranger came and sat right next to you when spare double seats were available…. you’d ring the bell and get off pretty quickly!

So people naturally sit on their own double seat if possible, only pairing up with a stranger if absolutely necessary. It is the same for electrons; at one energy level, electrons will always go into separate orbitals if possible (Hund’s Rule). One way of understanding this fact is that electrons in the same orbital are in the same region of space and, since both are negatively charged, will repel each other.

The bus doesn’t have a ready analogy for spin, but for other aspects of filling up energy levels it is very good.

Examples to illustrate the key ideas

Finally, a set of examples to illustrate the key ideas in this section.

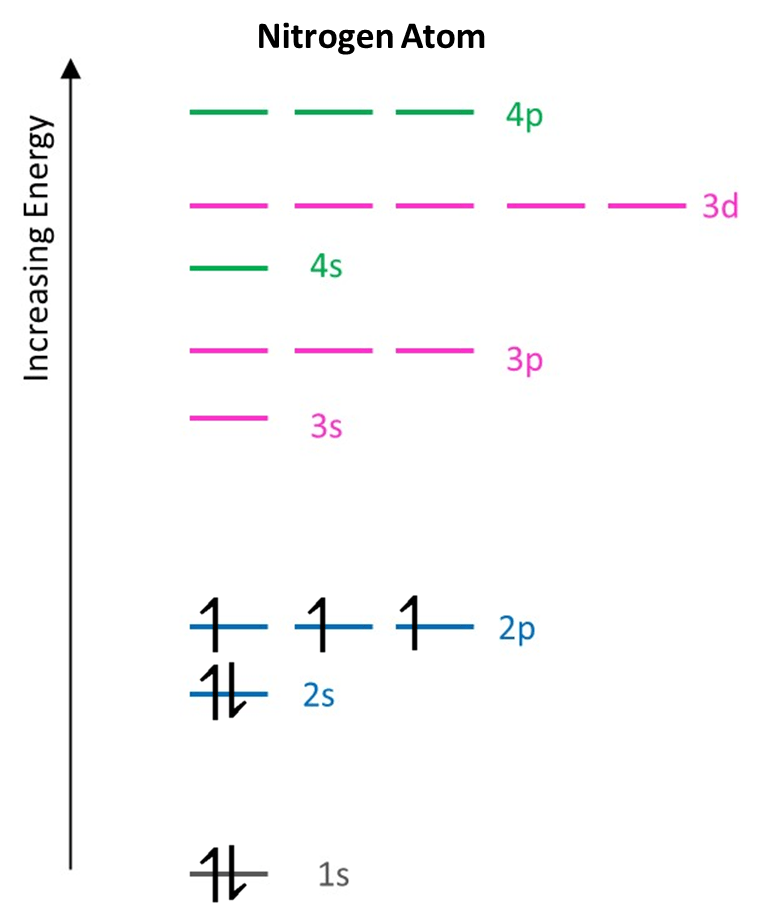

Example 1: Nitrogen atom

A nitrogen atom has 7 electrons. We can apply the three rules above to work out how the electrons are organised in the energy levels of a nitrogen atom.

Following the Aufbau principle, the first electrons will go into the 1s subshell as it has lowest energy. After two spin-paired electrons have filled that orbital (Pauli principle), the 2s orbital is the next lowest in energy, so fills with electrons. That can also take two electrons, leaving 3 more electrons for the 2p subshell. Hund’s rule then requires that these electrons are spread equally among the orbitals of the 2p subshell. The spins of these three electrons in orbitals in the same subshell must be the same. The situation is then:

The electron configuration is then written by listing the subshells in order of energy (from lowest to highest) and indicating with a superscript the number of electrons in the subshell. For nitrogen, the electron configuration is then:

N: 1s2 2s2 2p3

In total, 3 subshells (energy levels) contain electrons which are spread among 5 orbitals.

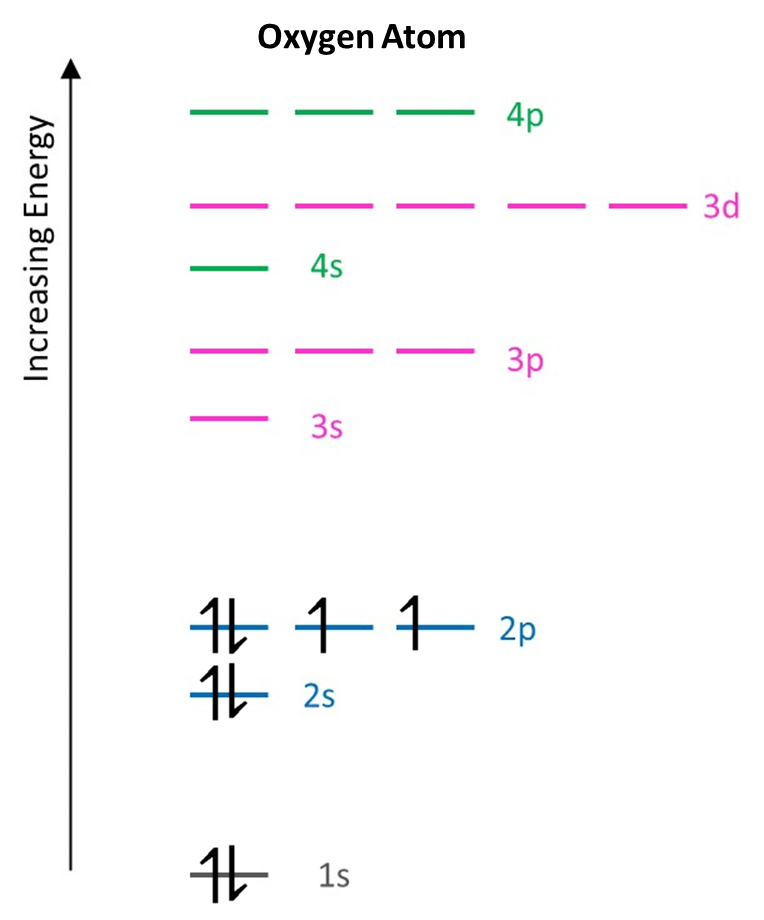

Example 2: Oxygen atom

An oxygen atom has 8 electrons. Obviously the first seven of these are distributed in the same way as the nitrogen atom. When an eighth is added, it must now go into one of the singly occupied 2p orbitals, with opposite spin to those already present:

For oxygen the electron configuration is then:

O: 1s2 2s2 2p4

In total, 3 subshells (energy levels) contain electrons which are spread among 5 orbitals.

Order of sub-shell energies

It is worth noting that there is an overlap of sub-shells from shell 3 and shell 4; the 4s energy level appears between the 3p and 3d levels and so the Aufbau Principle indicates that 4s fills before 3d. This is evident when the electron configurations of potassium and iron are determined:

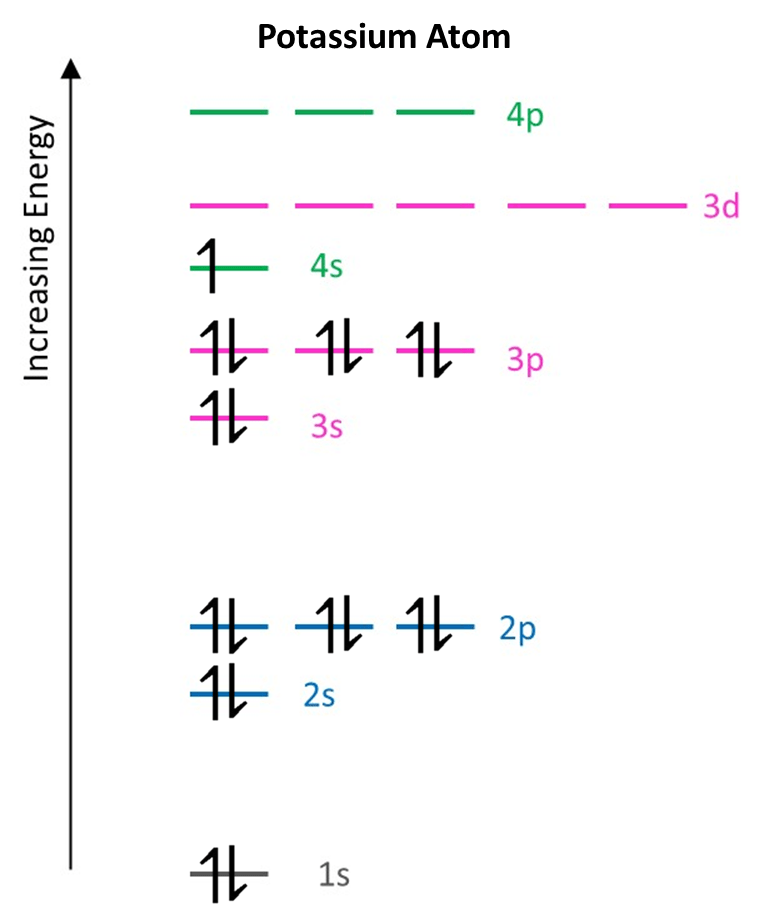

Example 3: Potassium atom

A potassium atom has 19 electrons. Following the same set of rules as before means that once 18 electrons have been added each orbital in the 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s and 3p subshells is full, with two electrons of opposite spin. The 19th electron must then go into the subshell with next highest energy; this is the 4s subshell, even though another subshell from shell 3 remains unoccupied at higher energy (3d). The electron configuration of potassium is then:

For potassium the electron configuration is then:

K: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s1

In total, 6 subshells (energy levels) contain electrons which are spread among 10 orbitals.

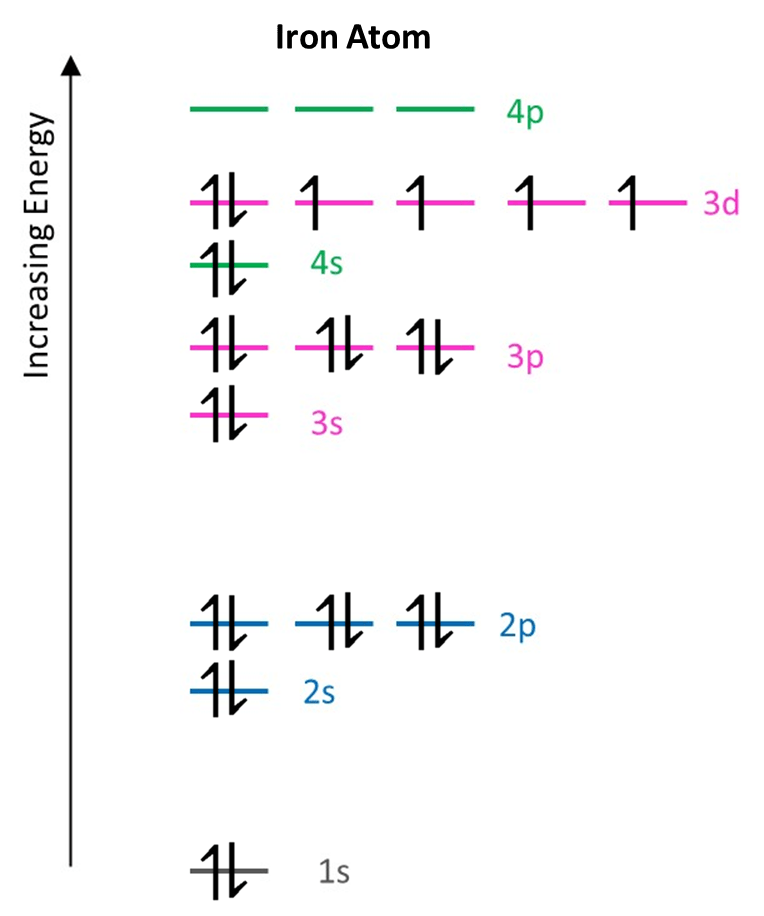

Example 4: Iron

An iron atom has 26 electrons. The electron configuration of iron can be found by adding a further 7 electrons to the arrangement of potassium shown above. One more electron will complete the 4s subshell and so the final six will enter the 3d subshell; occupying orbtials singly at first and only pairing up when the 26th electron is added. Hence, shell three continues to fill even after two electrons have entered one subshell of the fourth shell.

The electron configuration of iron is then:

Fe: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d6

In total, 7 subshells (energy levels) contain electrons which are spread among 15 orbitals.

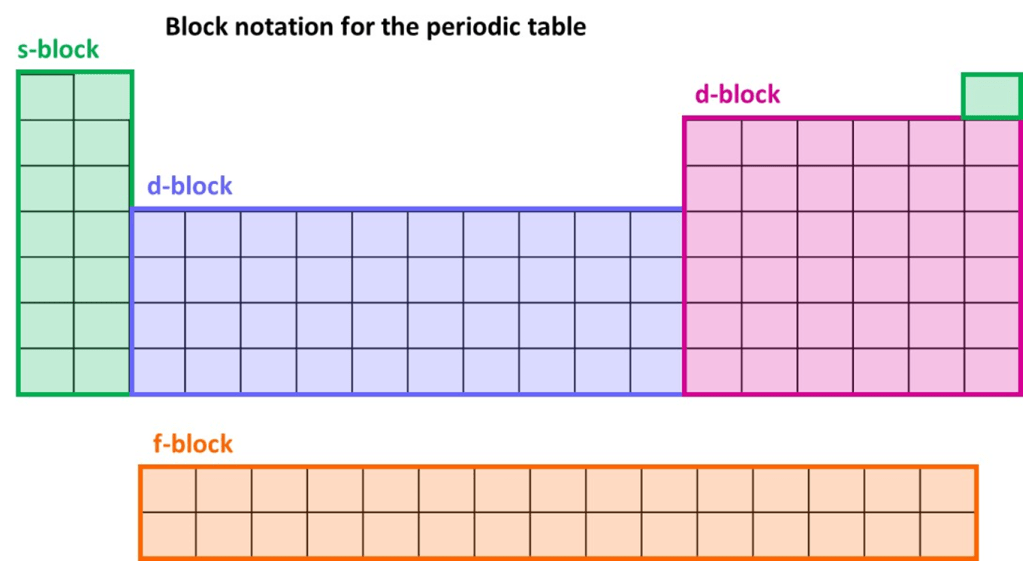

Linking electron configuration to the periodic table

The periodic table can be conveniently divided into four “blocks” which are then linked to the electron configuration of elements. This is shown in the figure below:

Hydrogen and Helium, which are not displayed in the same location on every periodic table are part of the s-block. The diagram slightly simplifies the situation because the f-block is inserted into the region shaded blue and electron configurations are more complex around that region.

However, for the vast majority of cases the block in which the element is located indicates the type of sub-shell in which the highest energy electrons are located. Furthermore, the group (vertical column) in which the element is located matches the number of electrons in that highest energy sub-shell. The four examples illustrated above will highlight this idea.

The highest energy subshell in nitrogen contains 3 electrons, 2p3. Nitrogen is located in the p-block and is the third group into the p-block in order of increasing atomic number. See the diagram below.

Oxygen is in the next group to the right of nitrogen and it’s highest occupied subshell contains 4 electrons, 2p4. Oxygen is located in the fourth group into the p-block.

Potassium is the first element in the s-block along period 4 and has highest energy subshell of 4s1.

Finally, iron is the sixth group along in d-block, with highest energy subshell 3d6. Note that although iron is in period 4, the highest subshell is 3d not 4d. This simply reflects the order of energy of the subshells, no d-subshell has an energy below the 4s subshell, so the shell number for d-subshells will always lag behind the period number. This applies to all d-block elements.

This means that it is now possible to deduce the configuration of the highest energy shell in an atom, without having to work out the entire configuration. There are a small number of d-block elements for which this doesn’t work (and the f-block is more complex) but generally, you can find the occupancy of the highest energy subshell by counting the number of groups into the block (in order of increasing atomic number) and find the shell number by identifying the period.

For example, the element iodine, is the fifth group into the p-block, and the fifth period, so the outer electron configuration will be 5s2 5p5. Similarly, rhodium is the seventh group into the d-block and the fifth period, so 4d7 (remember the lag).

Noble gases

The noble gases are the final group in the p-block. With the exception of helium (1s2) the electron configurations are all of the form ns2 np6 where n is the shell number. Since the number of electrons in a shell is given by 2n2 and exceeds 8 electrons after shell 2, it is not correct to say “the noble gases have a full outer shell”, but rather a full “p-subshell”. This will allow us to see how noble gases can form covalent molecules in a later section.

Electron configurations of simple positive ions

Simple positive ions are formed when atoms lose electrons, so that the total number of protons exceeds the number of electrons. The electron configuration of a simple positive ion can be found by removing electrons from the electron configuration of the atom. Electrons are removed from the highest energy subshell first and in such a way that the Aufbau, Hund and Pauli rules are maintained. For example:

Mg atom: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2

Mg2+ ion: 1s2 2s2 2p6

There is a small complication to this process when forming positive ions of d-block elements, but since this is an introductory set of notes, this feature will be covered later.

Electron configurations of simple negative ions

Simple negative ions are formed when atoms gain electrons compared the the atom; the ion therefore has an excess of electrons relative to protons. The electron configuration of the ion is found by continuing to add electrons to the arrangement in the atom, ensuring that the rules for filling orbitals are maintained. For example:

O atom: 1s2 2s2 2p4

O2- ion: 1s2 2s2 2p6

“Copyright Simon Colebrooke 2nd April 2025”

Suggested next pages

To continue reading about electron orbitals and their shapes go to section 1.10.

Update history:

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk