Ancient Greek philosophers suggested that there were four basic elements and that every other substance was made from some combination of these. Their elements were Earth, Air, Fire and Water. For example, if a piece of wood was burnt, the presence of all four elements could be seen coming from the wood; the flames were the fire, the smoke rose and became part of the air, water boiled and spat from the burning wood and the ash left behind afterwards had properties like Earth. All four elements had been present in the wood in various amounts. But like the Ancient Greek ideas about atoms, their view had some truth to it (there are indeed fundamental chemical substances) but it was a philosophical point and not based on any scientific evidence.

Nowadays – instead of only four – we have 118 chemical elements, organised into the famous Periodic Table of the Elements. Earth, Air, Fire and Water are not amongst them anymore, so what is our understanding of an element?

A not very helpful definition of “element”

Understanding what is meant by an element is obviously going to be an essential part of learning chemistry. However, over the years I’ve actually found many students struggle to understand the modern meaning of an element. And no wonder actually, because when I first started teaching the student text book (aimed at 11-14 year olds) defined an element as “a substance which cannot be chemically broken down into anything simpler” or words to that effect. Clear as mud! With definitions like that to help you, chemistry is going to be a tough challenge and I remember reading and struggling with similar definitions myself.

Of course, I get the idea of that statement – elements are the simplest things in so much as you cannot separate other substances from them, or get any other chemicals out of them. However, that’s the kind of definition an early Victorian chemist might have found useful 180 years ago, as they experimented away in their labs surrounded by bubbling flasks, countless bottles of mysterious chemicals, free to spend their days sticking electrodes into things.

As a student in the 2020s you’re hardly in the same position. Things have moved on in terms of health and safety and, alas, your teachers are unlikely to allow you to gather up gallons of urine, then boil it down into a paste to see if you can get any phosphorus from it (as the alchemist Hennig Brand did in the 1660s). So you won’t be able to tell whether it is possible to get “simpler things” from a substance or not.

And you certainly can’t tell by looking at real objects either. For example, how could you from their appearance whether a lump of iron (element) is simpler than a lump of steel (not an element)? Or is the colourless gas carbon dioxide (not an element) more complicated that the colourless gas nitrogen (element)? From what you can actually see, the substances within these two examples look more or less exactly the same! Throw in the fact that the same element can have several different forms (e.g. diamond and graphite are both the element carbon but don’t look alike at all) then the “something simpler” type of definition is unlikely to help someone just starting out learning chemistry.

Fortunately, now that we understand a lot more about atomic structure than the early chemists did, we can have a much better definition of an “element”. This will make it easier to tell if something is an element or not, although you still won’t be able to tell just by looking at it – you’ll have to know about the structure of the atoms within it.

A good definition of “element” that uses atomic structure

The best way of understanding chemical elements now is this:

So all the atoms within a sample (piece) of an element must have the same number of protons.

With this definition it is quite easy to explain the examples mentioned above:

- Carbon dioxide is not an element because it contains two sorts of atoms that differ in the number of protons; the carbon atoms have 6 protons each, whereas the oxygen atoms have 8 protons.

- A sample of oxygen, is an element, because it only contains oxygen atoms and they all have 8 protons.

- Iron is an element, because all the atoms within it have 26 protons, but steel is not an element, because some of the atoms have 26 protons (the iron), some have 6 protons (carbon) and some have other values (such as chromium with 24 protons) in the case of stainless steel.

Notice that the definition does not have anything to say about neutrons (or electrons). So the atoms within an element can have different neutron numbers so long as the protons are the same. This means that a sample of an element can contain any number of different isotopes.

The 118 Chemical Elements

At the time of writing there are 118 confirmed chemical elements. Every element from atomic number 1 (Hydrogen, H with 1 proton) to atomic number 118 (Oganesson, Og with 118 protons) has been discovered. However, several laboratories around the world are actively attempting to create new ones, so I doubt 118 will be the total number for much longer.

Approximately 90 of the elements are naturally occurring, the rest are synthesised in labs or are products formed in nuclear reactors. The naturally occurring elements are mostly those up to Uranium, with atomic number 92.

There is a huge range and variety of properties amongst the elements. Around two-thirds are metals. Some are highly reactive (e.g. rubidium and caesium), some are extremely unreactive (e.g. gold), there are colourless gases (e.g. nitrogen), toxic gases (e.g. chlorine), yellow solids (sulphur), highly poisonous metals (e.g. lead) and only two liquids (mercury and bromine). The reasons for some of this variation will be covered in the later periodic table sections.

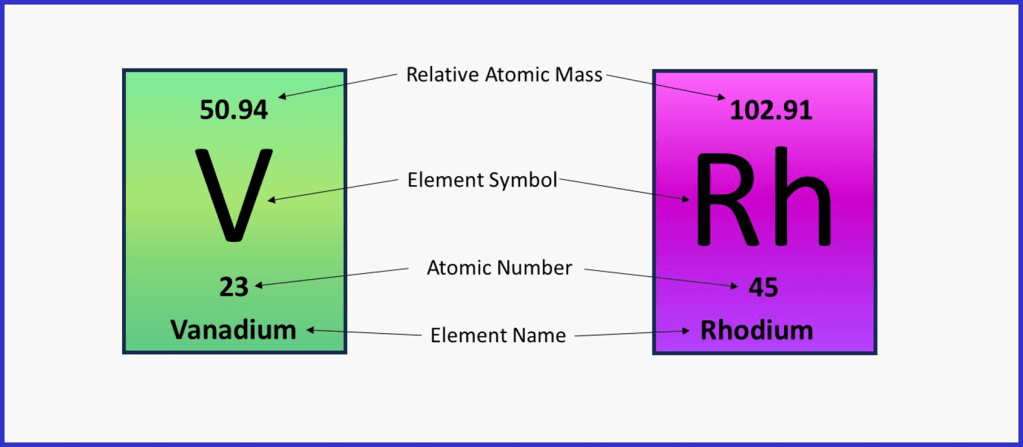

Each element has a cell on the periodic table and a unique symbol to represent it, either 1 or 2 letters long, the first letter always being a capital and the second always lower case. For example, Vanadium V and Rhodium Rh.

Most periodic tables show the elements in cells rather like the examples in the diagram below, although the exact location of the different numbers and symbols within the cell can vary according to the design.

All the millions / billions of other chemical substances which are not included in the periodic table are made from combinations of these 118 elements joined together in some way. The Ancient Greek element “air” is now known to contain oxygen, nitrogen and argon amongst other things, whereas the “water” is known to contain hydrogen and oxygen. Those ancient elements could have been “broken down into simpler things” had they been able to do the right experiments, so they don’t count as elements now.

However, I think you’ll find recognising elements by the number of protons a much more useful way forward in

A-level chemistry.

“Copyright Simon Colebrooke 17th April 2025″.

Update history:

Minor rephrasing and some corrections 8th May 2025.

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk