Think of almost any commercial product and there is a good chance that someone, somewhere has printed a periodic table on one and tried to flog it! I’ve seen them on mugs, coasters, note-books, water bottles, ties, t-shirts, socks, pens and tea towels. Of course there is also one on the wall in every school/college science lab and they are often on text book covers, exam data sheets and so on. There is no doubting the significance of the Periodic Table and it has become the most recognisable icon of chemistry.

However, the one we’re used to looking at actually differs quite significantly from the one first published by Dmitri Mendeleev in 1869. Some of the most significant differences are listed below:

1. The number of elements

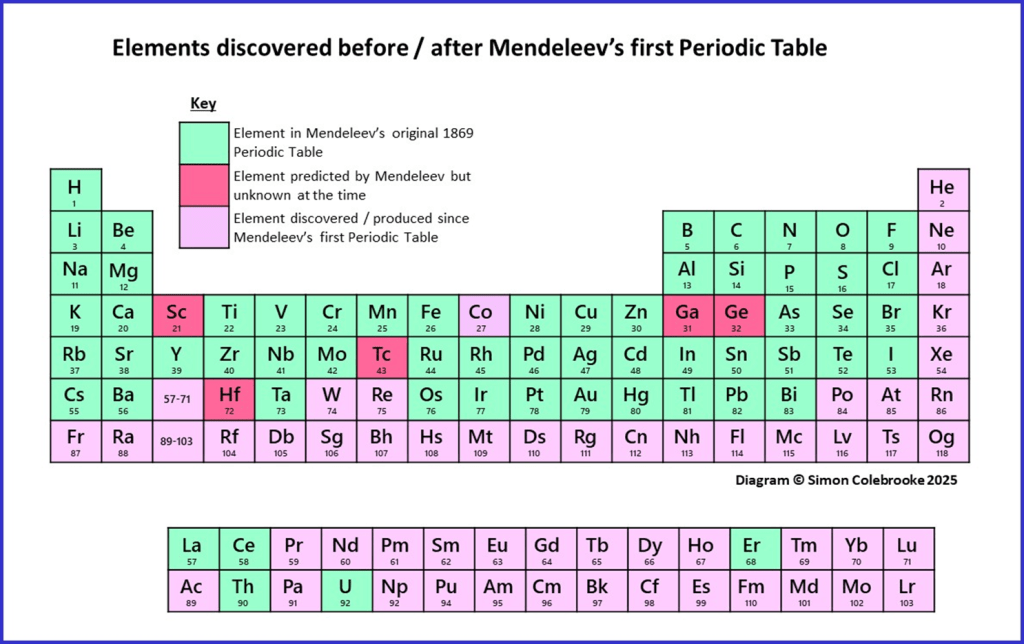

Firstly, Mendeleev’s original table from 1869 only contained around 60 elements, as they were the only ones discovered at that time. Modern Period Tables now show 118 elements, meaning that about half the elements have been discovered since Mendeleev’s first table was published. Some of the elements he included have since been found to correspond to more than one modern element. Two of the most notable additions are Gallium (Ga) and Germanium (Ge), as it was Mendeleev’s predictions about these elements that were crucial in getting his table accepted. However, many other important elements which we are familiar with were absent from his table. For example, none of the noble gases were present in the first table (now group 18 in the version I’ve shown below, from Helium to Radon), although evidence for a new element was just being obtained and was quickly confirmed to be Helium.

Most of the “Lanthanides” (elements 57-71) and “Actinides” (elements 89-103) were also absent, along with all the synthetic elements produced in nuclear reactions since the 1940s. The location of elements discovered before and after Mendeleev’s first periodic table are indicated in the diagram below:

You can see from the diagram that most of the elements we are familiar with were known by Mendeleev; it is the elements with much higher atomic mass that make up most of the new discoveries.

2. The order of the elements

It is important to remember that in 1869 chemists did not have the knowledge of atomic structure that we do; even the electron was not going to be discovered for another 27 years. So, the elements were simply placed in order of increasing atomic mass, except for a few cases where it was necessary to reposition some elements to keep elements with similar properties in groups. To Mendeleev, the atomic number was just the position of an element in the sequence obtained when they were arranged in order of increasing mass.

Moseley’s discovery of the proton had the consequence that chemists found the atomic number is actually related to a structural feature of atoms (the proton number). Now the elements are now strictly ordered by atomic number and there are no exceptions and no need to switch some positions in order to help the group properties match better. For example, this means that the elements Iodine and Tellurium which Mendeleev had to place out of mass order, now follow the sequence of increasing atomic number.

3. Grouping by chemical properties

If you have already read section 2.3 you are aware of how Mendeleev attempted to use the properties of the elements he knew to arrange them in groups that exhibited similar behaviour. Given that he had an incomplete list of elements and quite limited data he did an incredible job – so much of his table is still recognisable 150 years later. However, he did place some elements in places that seem surprising to us now and which you could think of as errors. For example, he placed Aluminium, Uranium and Gold all in the same group! Barium and Lead also appear in the same group of Mendeleev’s table, and all these examples are spaced well apart now.

4. Gaps

Part of Mendeleev’s genius was to realise that some elements remained to be discovered. This might not seem such a leap now, but with our knowledge of atomic structure we know so much more about what makes elements different and could easily tell if another was expected somewhere, due to the gap in atomic number sequence. His realisation meant that he left a number of gaps where he suggested elements ought to be. However, our modern Periodic Table has no gaps at the moment; all the elements from 1-118 have been discovered, each with a unique atomic number. At present all the groups and periods look complete, although when new elements are eventually synthesised in the years ahead that will change. Gaps may exist between some elements again. However, when that happens, we will know for certain what the atomic numbers of the missing elements are and where they will sit in an expanded table.

5. Link to atomic structure

As stated above, there were obviously no links between the location of an element in Mendeleev’s table, and the structure of the atoms of that element. Nowadays chemists can use the position of an element in the Periodic Table to tell a great deal about the structure of the atoms of an element. For example – information about the number of protons and electrons, the number of electron shells, the number of electrons used for bonding, the amount of energy needed to take electrons away from atoms, the size of atoms – these can all be determined simply by looking at the position. The way this is done will be described more fully in the next notes section.

6. Modern Periodic Tables are rotated relative to Mendeleev’s original

Mendeleev’s original table in 1869 positioned the elements horizontally next to those with similar properties. However, nowadays this arrangement is vertical and the series of elements called a “group”.

Similarly, on Mendeleev’s original Table, elements involved in repeating patterns in properties occurred vertically and, overall, atomic mass increased in sequence down his table. In modern versions, these sequences run horizontally instead and these series of elements are called “Periods”.

In effect, the periodic table has been rotated. Our modern meaning of “Group” and “Period” is shown in the diagram below. This arrangement means that we have a total of 18 Groups (numbered in blue from 1-18) and 7 Periods (numbered in orange from 1-7). Other numbering systems for groups and periods are used as well, depending of style preferences. I’ll mostly stick to the ones in my diagram, but probably won’t all the time! Our modern table actually has slightly fewer groups and periods than Mendeleev’s, mainly because he had so much uncertainty about the number of elements and limited data on their properties.

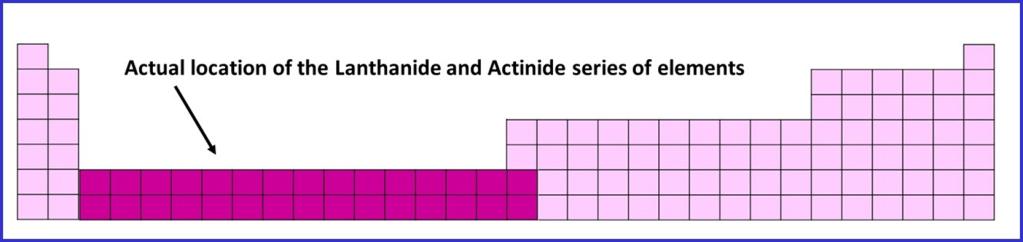

The Lanthanides and Actinides are usually placed beneath the rest of the table, to avoid it becoming too long, with some colour / symbols used to indicate where they should be inserted in the full table. In it’s correct place it would look like this, sitting between groups 2 and 3. I haven’t seen a numbering system for these groups and if there is one, it is rarely used.

7. Block system

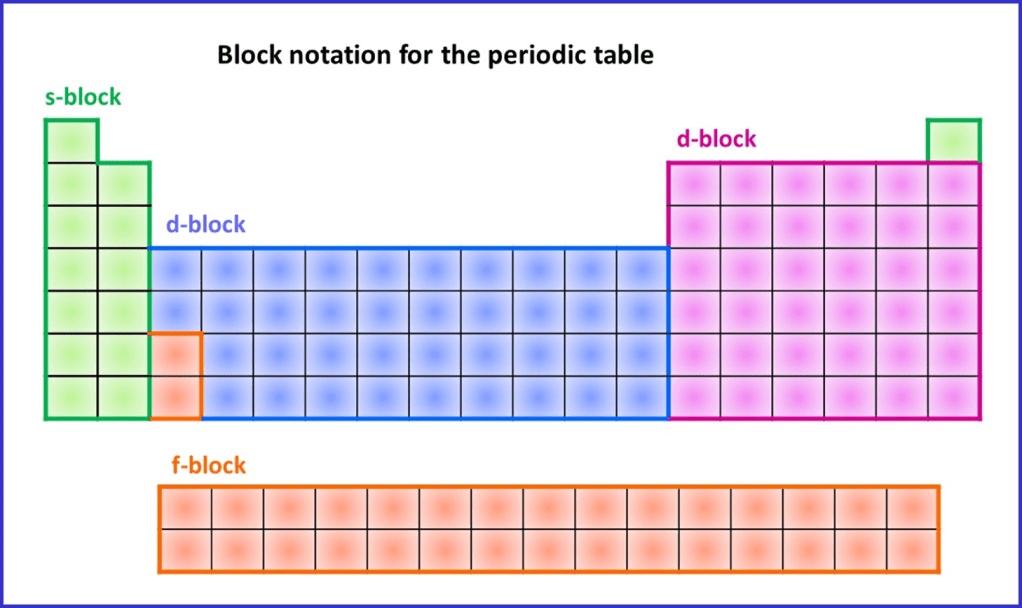

The modern Periodic Table is divided up into four regions called “Blocks”. There are called the s-, p-, d- and f-blocks (linked to electron sub-shells) and are located as follows:

The main use of the Block system is determining electron arrangements in atoms – more in the next section.

8. Inclusion of isotopes

Isotopes are atoms of the same element with different numbers of neutrons and hence, different atomic masses. These were effectively unknown in Mendeleev’s time as neutrons were not discovered for another 50-60 years. However their presence is reflected in the modern table as almost every cell contains a value for the Relative Atomic Mass (RAM), which is an average mass for the element considering all the isotopes and their relative proportions.

10. The position of hydrogen

Where does the element Hydrogen belong on a Periodic Table? This is still not universally agreed! For some reason, Mendeleev put hydrogen with copper, silver and mercury, though I can’t think of many properties those elements have in common. Nowadays, hydrogen is usually located at the top of Group 1 just above lithium although in many ways, it doesn’t really fit to well there either. Sometimes it even just hovers lonely on it’s own, vaguely above the rest of the table and not attached to anything else.

11. Element symbols

Finally there are some fairly cosmetic differences between Mendeleev’s table and the modern table, in that some element symbols have changed. He used Ur for uranium (now just U), J for iodide (now I, whereas J is related to the German name) and Yt from Yttrium (now just Y). He also included an element Didymium, Di, which was later found to not to be an element at all but a mixture of Praseodymium and Neodymium. Element symbols now are internationally agreed and regulated by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry – IUPAC for short.

Conclusion

So why has the Periodic Table become so instantly recognisable? I think it’s several reasons; the interesting story of it’s development and the chemists who contributed to it, including Mendeleev the stereotypical mad-scientist / genius who finally solved the problem. However, in addition to that, it’s also amazingly clever, tying together the enormous variation in properties found amongst the chemical elements. Once you’ve understood how it works, you can quite accurately predict how different elements will react and what their compounds will be like… basically… it’s incredibly useful and modern chemists would be lost without it.

Copyright Simon Colebrooke 7th May 2025.

In writing this article I referred to a translation into English of Medeleev’s original paper from 1869: On the Relationship of the Properties of Elements to their Atomic Weights. D. Mendelejeff, Zeitscrift fur Chemie 12, 405-406, 1869. Translated by Carmen Giunta.

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk