Section 1.9 introduced the concept of ionisation energy, describing why energy is needed to remove electrons from atoms and how the required energy increases with each electron removed. This was successive ionisation.

This section is going focus only on the first ionisation energy but describe how it varies between elements in the periodic table – because the trends are quite systematic. Analysis of this sort supports the electron structure of atoms described in section 1.8. As a reminder, here is an equation defining the first ionisation energy when it is carried to form 1 mole of positive ions (6.02 x 1023 ions):

Factors that affect the size of the ionisation energy

When ionising an atom with this definition of first ionisation energy, an the electron in the highest energy subshell will be removed first.

Before looking at the trends it is worth pointing out that the size of the first ionisation energy can be understood in terms of these three factors:

1. The distance of the outermost / highest energy subshell electron from the nucleus.

2. The size of the positive charge in the nucleus – how many protons are present

3. The amount of shielding the outer electron experiences because of the repulsions of inner electrons between it and the nucleus.

The way in which the first ionisation energy varies through sequences of elements along periods or down groups on the periodic table will be determined by how those three factors change.

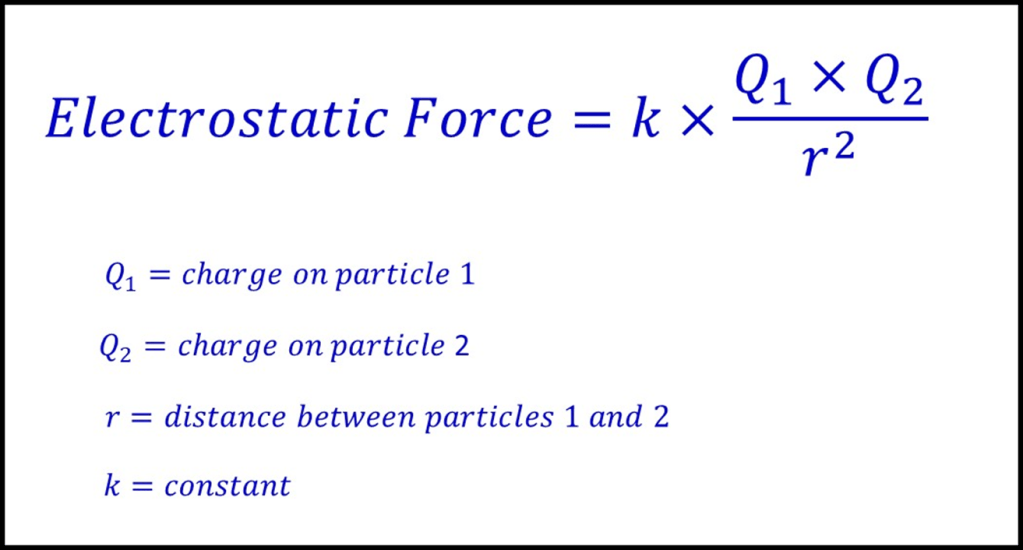

Section 1.9 also introduced Coulomb’s law, which is shown again below. It shows that the size of the electrostatic force attracting the electron to the nucleus is proportional to the size of the charges involved (affecting factors 2 and 3) but inversley proportional to the distance squared. This means that if more than one factor changes at a time the change in distance is likely to be most significant.

To see why that is the case, think about what would happen if the magnitude of one of the two charges involved was increased. In the case of ionisation the two key charges to consider are the outer electron and the nucleus. If the charge on the nucleus was doubled (by increasing the number of protons) the force between the electron and nucleus would also double. This is because in Coulomb’s law, the force is directly proportional to the charge.

If however, the distance between the outer electron and the nucleus was doubled the force would be reduced to a quarter of it’s original value. In terms of ionisation this means that the electron is in a higher energy subshell and so on average further from the nucleus.

Although this is a significant simplification of the situation in a real atom, it gives us a useful feeling for how differences between two atoms will be reflected in the first ionisation energy.

Now we can look at the trends:

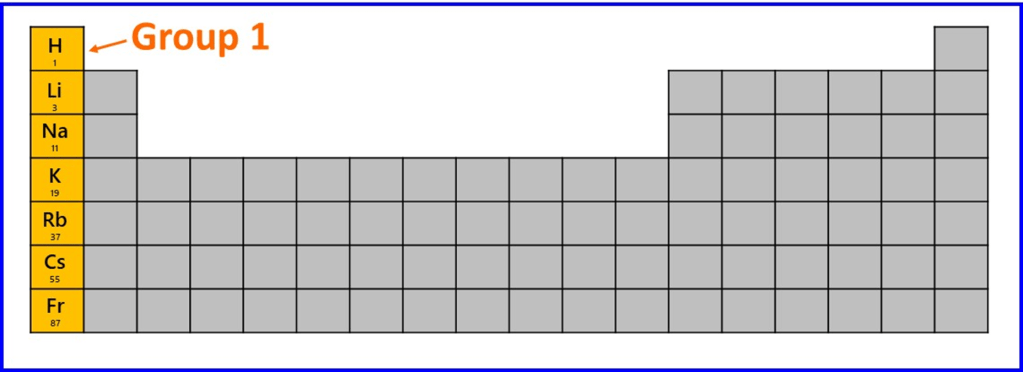

A). Trend down a group

First, we’ll look at the elements in Group 1, from hydrogen to francium and think about what changes about the atoms of these elements. All of these atoms have one valence electron in an s-orbital.

As we move downwards through this series of elements the following changes occur:

i). The s-subshell containing the valence electron belongs to a higher shell number; n = 1 for hydrogen, n =2 for lithium and so on to n = 7 for francium. Therefore, on average, the valence electron in an atom of one element is further from the nucleus than the valence electron of the previous element in that group.

ii). More electron shells are present between the valence electron and the nucleus.

iii). More protons are present in the nucleus so that the nuclear charge has increased.

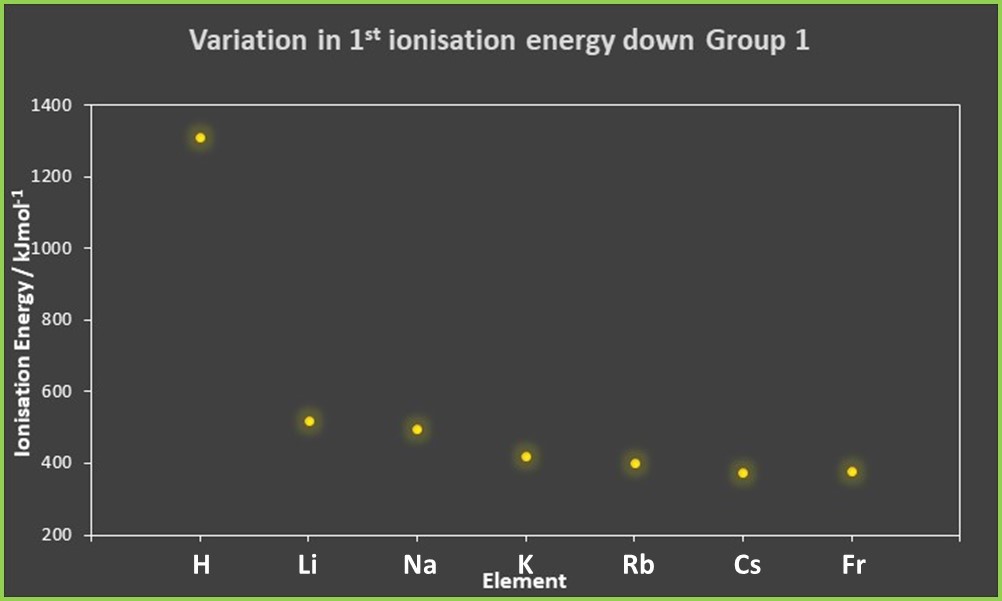

Plotting the values of the first ionisation energy against the elements in Group 1 gives the following result:

It is clear that (with the slight exception of francium at the bottom of the group) the first ionisation energy decreases for each subsequent element in the group, even after the huge reduction between hydrogen and lithium.

We can now rationalise these results in terms of the changes in atomic structure described in points i) – iii). All three of these factors change from H to Li and so on down the group. Both increasing the distance of the outer electron from the nucleus (point i) and increasing the amount of shieling by increasing the number of inner shells (point ii) should result in a weaker electrostatic attraction between the electron and the nucleus. However, increasing the number of protons in the nucleus would have the opposite effect and increase the strength of the electrostatic attraction. The atomic structure changes are shown in the diagram below:

The fact that the trend shows the ionisation energy decreases down the group means that the changes in distance and shielding outweigh the increase in atomic number. This is to be expected from Coulomb’s law, where we saw that the distance of the electron from the nucleus is the most significant factor.

Overall the changes in atomic structure mean that the electrostatic attraction between outer electron and the nucleus gets weaker down the group. Therefore less energy is required to remove an electron, resulting in a correspondingly lower value of the first ionisation energy.

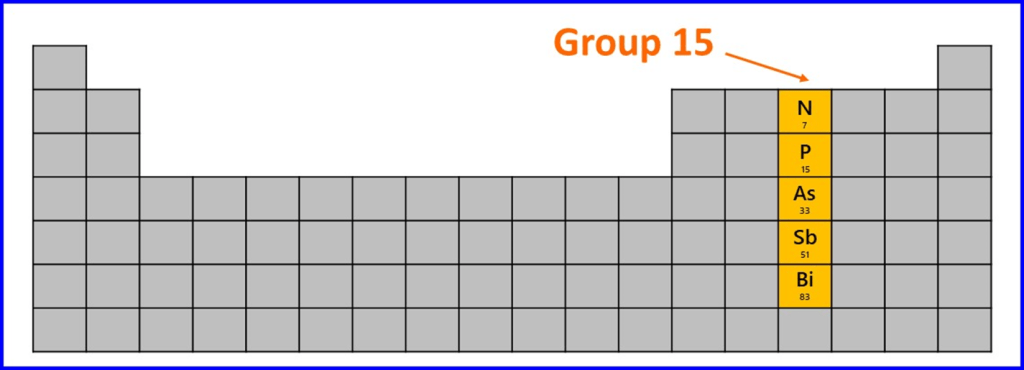

Similar trends are seen in other groups of the periodic table; the graph below shows the variation in first ionisation energy for the elements in Group 15 (N to Bi) and the same basic pattern is seen:

The same kind of changes in atomic structure occur through the series of elements N to Bi as happened from H to Fr; more protons in the nucleus, but this effect is dwarfed by the increases in electron to nucleus distance and shielding.

B). Across a period

What happens to the first ionisation energy across successive elements in a period (horizontal row) of the periodic table? The elements of period 2 will give a simple starting point for analysing this trend.

The first ionisation energies of these elements are plotted in the graph below.

Again, there is certainly a trend, although it is not followed universally. Overall, the first ionisation increases along the period towards neon, but on two occasions, there is a decrease between consecutive elements. So there are two questions to answer: a) why is there an overall increase? and b) why do some elements show a lower first ionisation energy than the previous one?

To understand the overall increase, we can think about how the three factors that affect the size of the ionisation energy vary across the period. Each successive element in period 2 has one more proton than the previous one, changing from 3 protons at lithium to 10 protons at neon. Thus, the positive charge in the nucleus increases for every element across the period. This obviously results in a stronger electrostatic attraction between the outer electron and the nucleus, increasing the amount of energy required to separate them.

By contrast, the amount of shielding hardly changes at all. Although the atoms of every element in the period consecutively gain one electron (as well as a proton) as the row is crossed, the electrons are being added to the same shell – the second shell for this period. Shielding is primarily caused by electrons in inner shells and so there is relatively little change in the amount of shielding across the period. Hence in most cases, the shielding has relatively little effect on the first ionisation energy across the period.

Finally, we should think about the change in distance of the outer electron from the nucleus. Section 2.2 explained that, (contrary to many students’ initial feelings), the atomic radius decreases across a period as the electron shells are drawn inwards by greater nuclear charge. Hence the distance between the outer electron and the nucleus actually decreases across the period, contributing to a stronger electrostatic attraction and increasing first ionisation energy.

Thus, the increase across the period is due to an increasing nuclear charge caused by more protons and a decrease in distance of the outer electrons from the nucleus. We would see similar trends in the next periods too, although complicated a little by the d-block elements, for reasons to be considered in a later section.

Exceptions to the overall trend

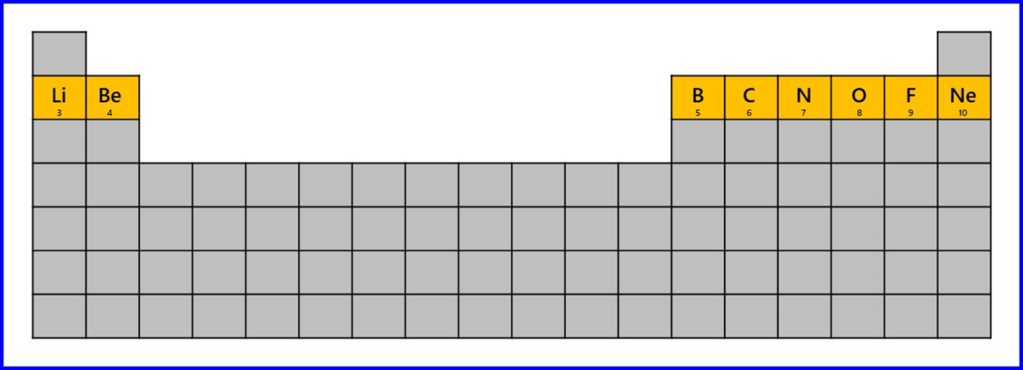

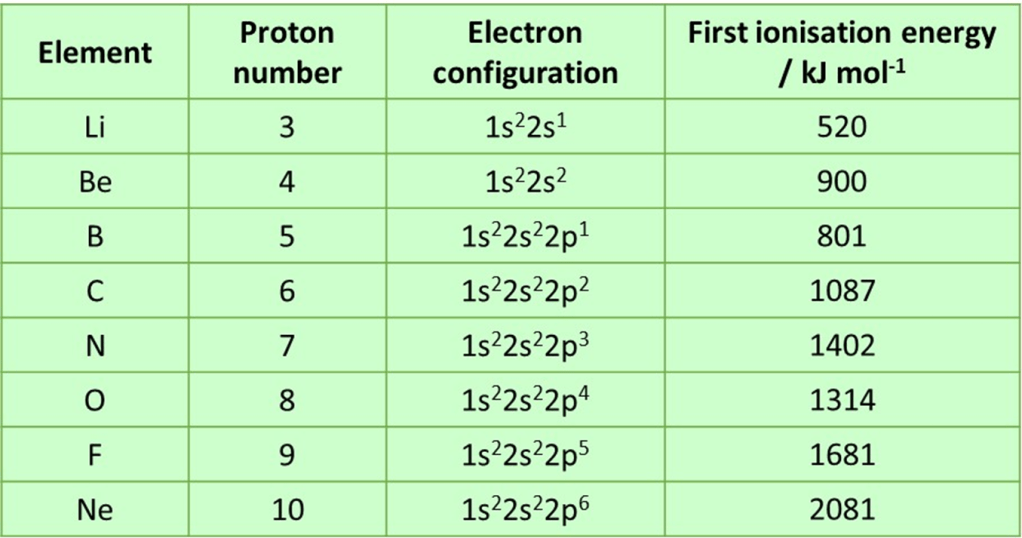

So why don’t all period 2 elements follow this trend? Why are some first ionisation energies lower than that of the preceding element? To explain this we need to think specifically about the electron arrangements of the elements in this period and they are summarised in the table below:

Boron

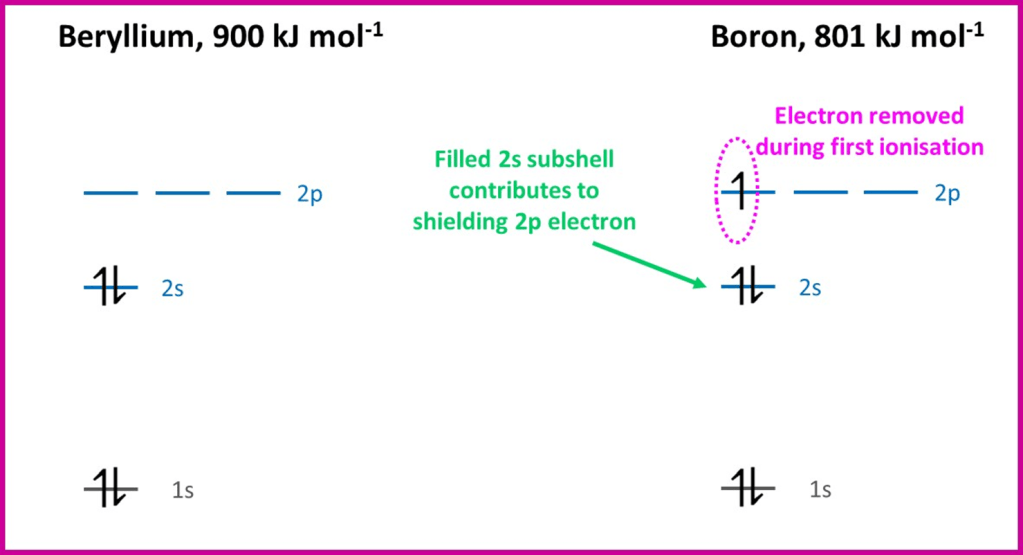

The first element with a lower ionisation energy that the previous element is boron. From the table we can see that boron is the first element to have an electron in the 2p-subshell. This subshell is slightly higher in energy than 2s (the electrons in 2p tend not to get as close to the nucleus as those in 2s) and so it is slightly easier to remove a 2p electron. The 2p sub-shell is also a little shielded by the 2s sub-shell; shielding is mainly caused by inner shells, but the spherical shape of the 2s orbital does mean the 2p electron in boron experiences some additional shielding. These factors more than compensate for the extra nuclear charge due to the added proton and so the first ionisation energy falls. After boron, electrons continue to be added to the 2p subshell but, each time another proton is included in the nucleus, and the first ionisation energy rises again; there is no accompanying change in shielding either as the later electrons continue to fill the 2p subshell. Comparing the electron energy level occupation of beryllium and boron helps to visualise the effect:

Oxygen

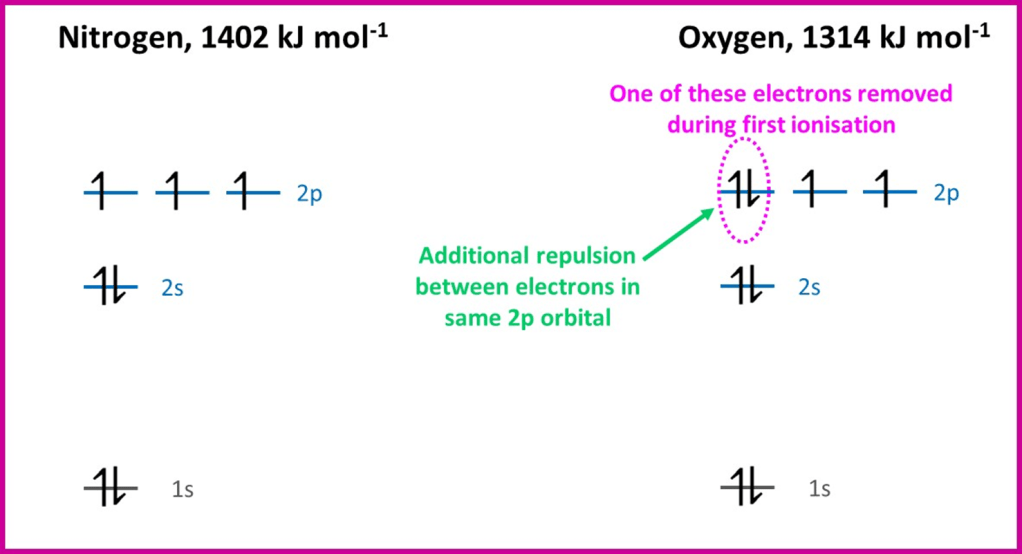

The other element which shows a lower first ionisation energy than expected by the overall trend is oxygen. The table above shows that oxygen has four electrons in the 2p subshell. The electron distribution amongst the orbitals is shown below for nitrogen (2p3) and oxygen.

Oxygen is the first element in period 2 to have a 2p orbital containing two electrons (at nitrogen each 2p orbital contained only one electron). Since orbitals are regions of space where we are likely to find electrons, we can expect two electrons in the same orbital (hence occupying the same region of space) to repel one another. This electron-electron repulsion reduces the first ionisation energy and so we can expect that it is one of these paired 2p electrons that is removed most easily.

After oxygen, although the additional 2p electrons are also going to be paired up with other electrons, the increasing nuclear charge means that the increase trend in ionisation energy resumes again.

“Copyright Simon Colebrooke 11th October 2025″

Suggested next pages

Click the icons below to either return to the homepage, or try a set of questions on this topic (choose the Q icon) or return to the notes menu (N icon).

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk