Introduction

Section 3.2 introduced the covalent bond in terms of electrostatic attractions, where atoms are modelled as sharing electrons that are attracted to both nuclei at once.

It also described the idea of the octet rule, which often correctly predicts the number of covalent bonds atoms form when joining together to make small molecules.

We can use these two concepts to draw diagrams that give a useful model of the arrangement of the atoms in the molecule and how electrons are shared.

The “Octet Rule”

There is not an obvious reason – based on the model of covalent bonding in the previous section – why the octet rule should work. Lewis pictured electrons as occupying the corners of a cube (8 corners in total) so that atoms shared electrons in order to fill these corners. However, although we no longer think of electrons adopting this arrangement, the octet rule persists because of how well it allows us to model an enormous number of molecules. We’ll look at an orbital overlap model of covalent bonds in future sections and then will be able to understand why atoms often end up with a share of 8 electrons (and why there are some occasions when they don’t).

The octet rule can be expressed as:

“Atoms share valence electrons with other atoms until they have a share of 8 electrons (excluding inner electrons) in the outer shell.

The very small atoms hydrogen and helium behave similarly, only their limit is a share of 2 valence electrons.”

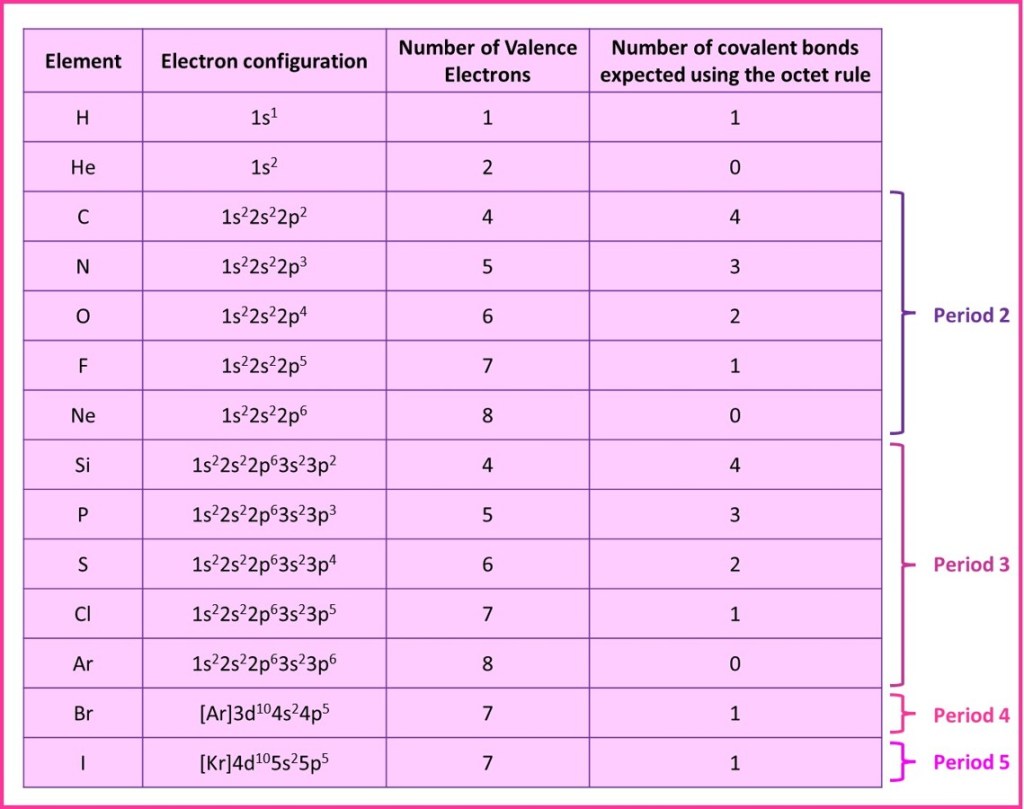

Usually when a covalent bond forms, a pair of electrons are shared with each atom contributing one electron. Thus, forming one covalent bond gives an atom a share of one additional electron (i.e. the electron provided by the atom it is bonding with). The table below summarises the number of covalent bonds some atoms would therefore be expected to form, if they bonded according to the octet rule.

For the period 2 elements carbon to fluorine – there is rarely an exception, these elements very often forming the number of bonds predicted by the octet rule. Similarly, neon with 8 valence electrons already, is extremely difficult to get to react and rarely forms any bonds at all. Hydrogen and helium also virtually always behave as shown in the table. The other elements in the table occasionally form a different number of bonds to that shown, but they still follow the octet rule often enough for it to remain useful and a good starting point in trying to understand the molecules formed by these elements.

So the octet rule is a useful rule of thumb and can usually be applied to covalent compounds involving the p-block elements. It is not sophisticated enough to predict the bonding from d-block and f-block elements.

Caution

I regularly hear students say things like “atoms want to get a share of 8 electrons”… of course, they don’t “want” to do anything. They’re not even thinking about it. They often end up with sharing particular numbers of electrons because it leads to a more stable arrangement than not sharing… But the atoms aren’t aiming for that, those things are just what happens to you when you’re an atom!

Covalent dot-cross diagrams

The arrangement of electrons in a molecule can be represented in a “covalent dot-cross” diagram, in which electrons from different atoms are drawn with different symbols (often dots and crosses – hence the name – although other symbols are used as well). The diagrams show the following features:

1) Atoms are represented by their element symbol, C for carbon, F for fluorine, Si for silicon etc.

2) Valence electrons that are part of the same covalent bond are drawn next to each other, in between the element symbols. These are bonding electrons, “shared” by both the atoms.

3) Valence electrons that are not in covalent bonds are drawn on the one atom they originate from. These are lone pairs of electrons.

There is no need to include inner shells of electrons or draw rings around the atom – the picture is intended to show how valence electrons are shared, not give a realistic appearance to the molecule.

Next are some examples of covalent dot-cross diagrams for molecules that do follow the octet rule:

Example 1: Methane

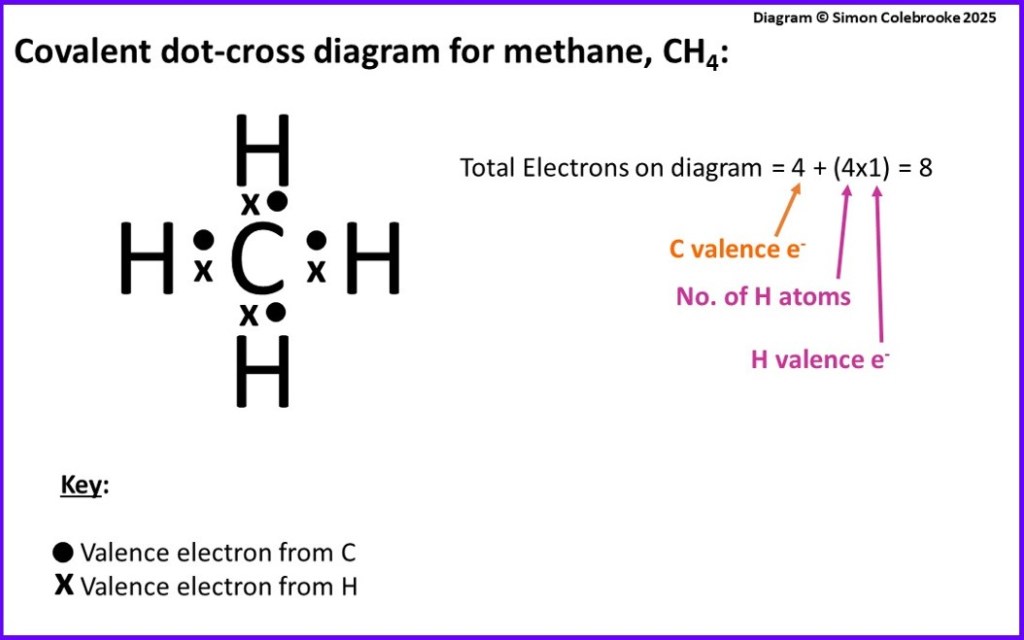

Methane, CH4, is a good starting point for drawing diagrams to represent the sharing of the electrons and seeing how the octet rule can be used to rationalise the bonding arrangement.

First, think about the number of valence electrons each atom has:

One carbon atom: 1s22s22p2, so four valence electrons (indicated in bold).

Four hydrogen atoms: 1s1, so just a single valence electron per atom.

Hence the total number of valence electrons in the molecule is 4 + (4×1) = 8.

The octet rule can be followed if the carbon atom shares one of its’ valence electrons with each hydrogen atom, whilst each hydrogen contributes its’ only electron to the bond. This results in the formation of four covalent bonds. Each hydrogen will gain a share of an electron from carbon, giving a total share of two electrons (thus meeting the octet rule for a small atom), whilst the carbon gains a share of four additional electrons, plus the original four electrons – totalling eight and thus meeting the octet rule.

Here is the covalent dot-cross diagram of methane, the “dots” showing the electrons from the carbon atom and the “crosses” electrons from hydrogen:

It is important to check that we have drawn enough electrons to show all of the valence electrons that are present (8 in total from the five different atoms in CH4). There are 4 shared pairs and no lone pairs in methane, so this is indeed a total of 8; all the valence electrons are drawn; four “dots” showing the electrons from the carbon atom, plus one “cross” from each hydrogen. The way in which the octet rule is met for each atom is indicated in the diagram below:

The methane molecule can also be represented by a structural formula. In this type of representation covalent bonds are shown as straight lines connecting the bonded atoms. Each line indicates a pair of shared electrons.

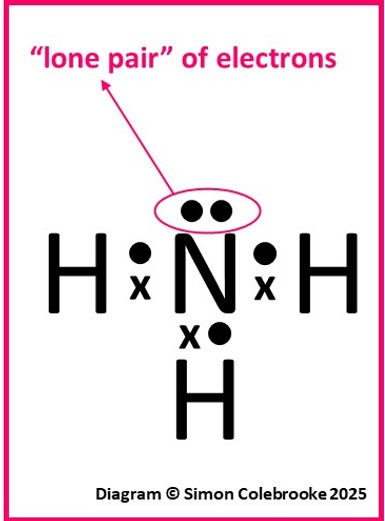

Example 2: Ammonia

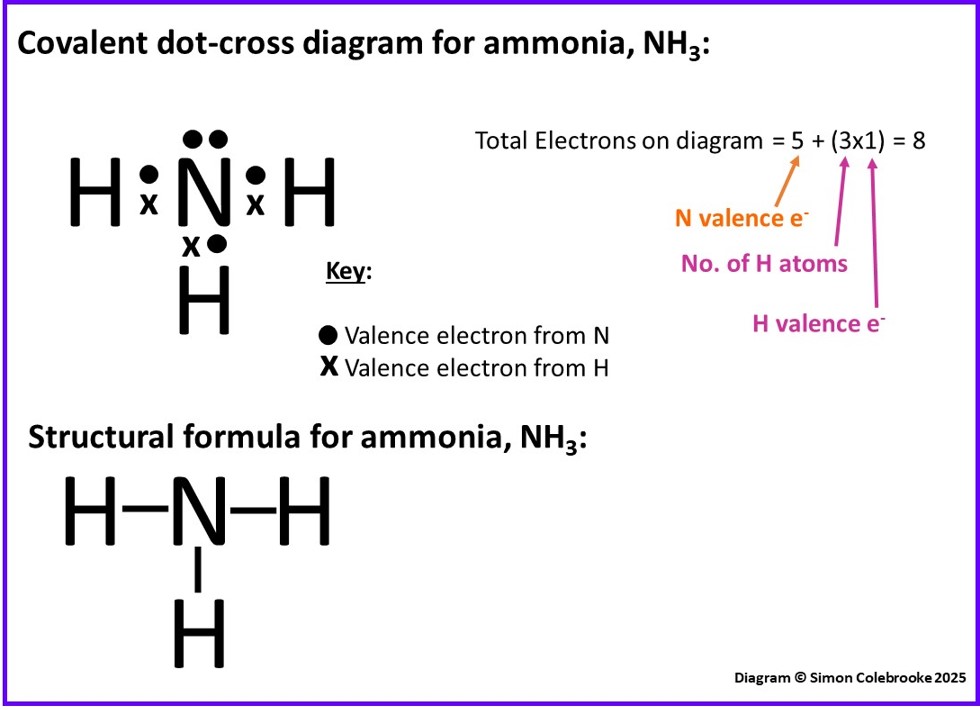

Ammonia, NH3, is a good second example. As before, we should think about the number of valence electrons each atom has:

One nitrogen atom: 1s22s22p3, so five the valence electrons indicated in bold.

Three hydrogen atoms: 1s1, so a single valence electron from each hydrogen.

Hence the total number of valence electrons in the molecule is 5 + (3×1) = 8.

The octet rule suggests that the nitrogen atom should form 3 covalent bonds and the hydrogen only one. This would result in the dot-cross diagram and structural formula shown below:

Notice that on this occasion, the nitrogen does not use all of its’ valence electrons as only three are needed to form the covalent bonds. The unused electrons are “non-bonding” and referred to as a lone pair. Although they are not involved with forming bonds in ammonia, lone pairs are critically important in determining some chemical properties and they affect properties like the shape of the molecule and bond angles – hence it is critical to identify them by drawing dot-cross diagrams.

We have drawn total of 5 “dots” (for the nitrogen valence electrons) and 3 “crosses” (for the hydrogen electrons). That is the expected 8 in total.

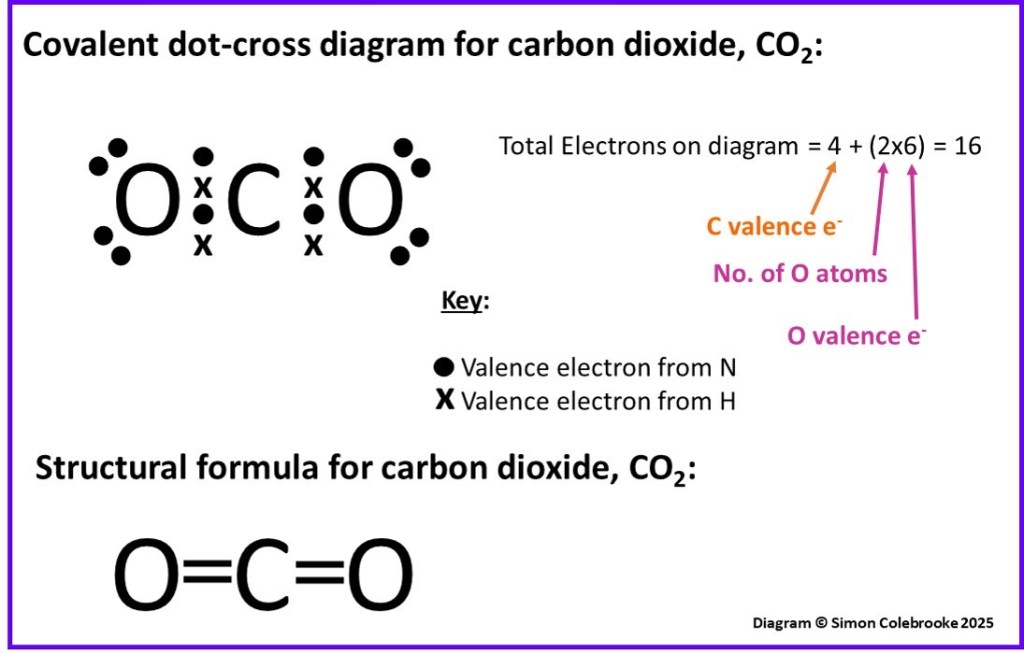

Example 3: Carbon dioxide

The CO2 molecule illustrates another aspect of covalent bonding. The valence electrons available this time are:

One carbon atom: 1s22s22p2, so four valence electrons.

Two oxygen atoms: 1s22s22p4 meaning six valence electrons per oxygen.

Hence the total number of valence electrons in the molecule is 4 + (2×6) = 16.

It obeys the octet rule so the carbon atom has to form four covalent bonds with only two oxygen atoms; it must therefore form two bonds with each oxygen. This is shown in the dot-cross diagram below:

Four electrons – two pairs – are shared between the carbon and each oxygen atom, which are double bonds. In a structural formula this is indicated by two lines between the bonded atoms, with each line representing two shared electrons.

With the remaining oxygen valence electrons added as lone pairs both atoms are drawn with a share of eight electrons.

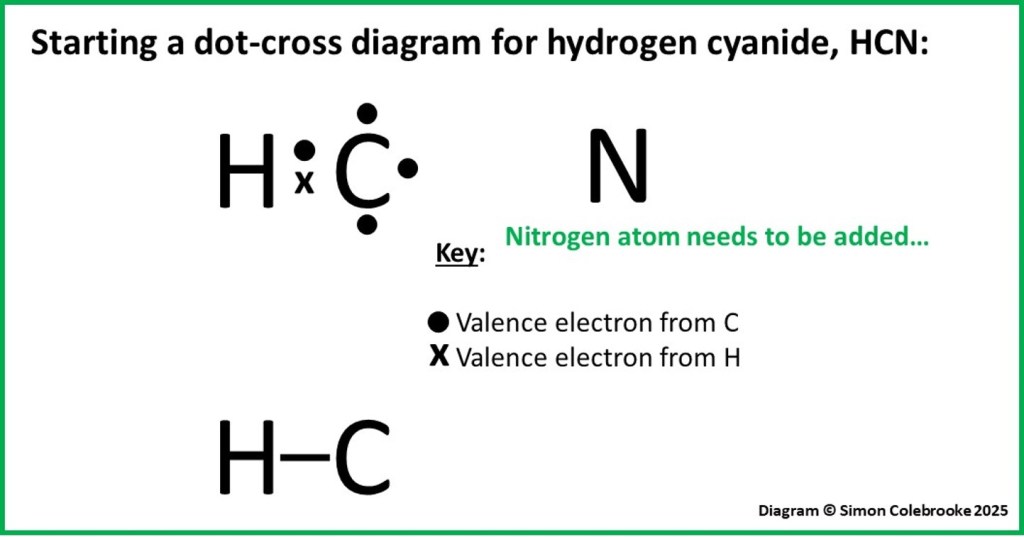

Example 4: Hydrogen cyanide

Hydrogen cyanide is a molecule containing one atom each of nitrogen, carbon and oxygen. We can use the octet rule to decide on a logical way in which these three atoms bond together and the order in which they are arranged in a molecule. Summarising the valence electrons contributed by each atom:

Carbon: 1s22s22p2, so four valence electrons.

Nitrogen: 1s22s22p3, so five valence electrons.

Hydrogen: 1s1, so a single valence electron.

Total valence electrons to draw = 4 + 5 + 1 = 10

How can these three atoms bond together? Firstly, according to the octet rule, the hydrogen atom can only form 1 covalent bond. Therefore, it must be at one end of the molecule, bonded to only one other atom. Does it bond to C or N? It makes most sense for the carbon to be at the centre of the molecule; it forms four bonds – more than any of the others – so could reasonably be expected to be at the centre, bonding to two other atoms. Hence, the hydrogen could bond to the carbon atom giving this arrangement:

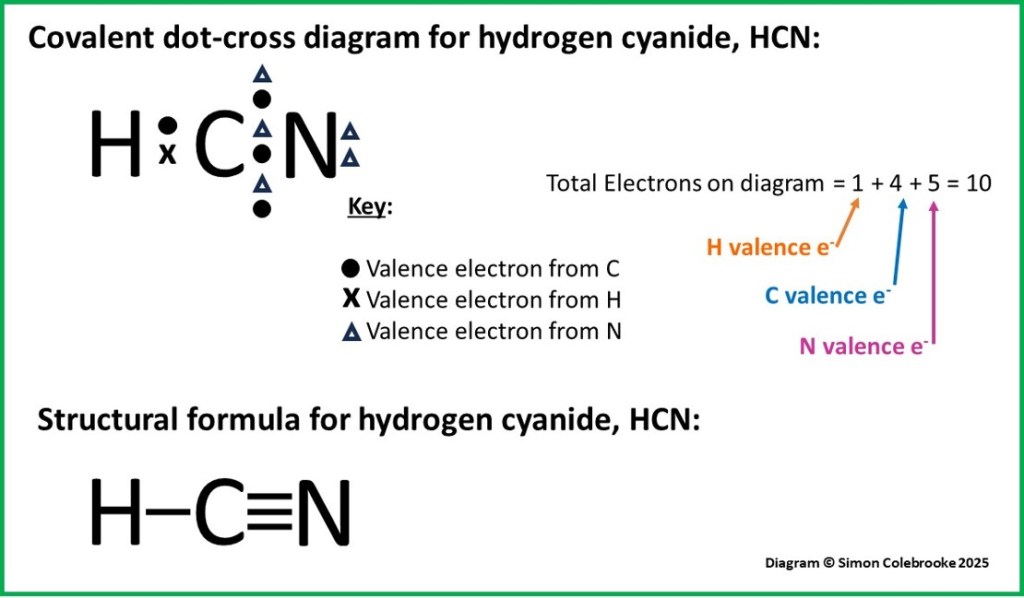

We expect a carbon atom to form four bonds, so if one of those is to hydrogen, it would need to form three more bonds with the nitrogen atom. This works out well, as nitrogen forms three bonds in the octet rule. As a result, we have the molecule shown below:

Our dot-cross diagram shows 10 electrons in total, as expected based on the valence electrons available from each atom. It is usual to show electrons from each element as a different type of symbol, so in this molecule, triangles are also used to represent nitrogen electrons.

Exceptions to the octet rule

The examples above have illustrated some relatively simple molecules where the octet rule is followed. However, this is not always the case. The model of bonding proposed by Lewis (with electrons arranged at the corners of cubes) does not fully explain why we’d expect atoms to form the number of bonds which they commonly do, and, in any case, we don’t picture their arrangement in this way anymore. Orbital models of covalent bonds do a better job of explaining the reason why the octet rule is apparently followed, so that now, this rule has become a useful guideline that often works.

We must be aware that there are many molecules that do not follow the octet rule. For example, some molecules are “electron rich” and in their dot-cross diagrams atoms have a share of more than 8 valence electrons. Others are “electron deficient” with shares of less than 8 valence electrons. There are also radicals, with odd numbers of electrons and molecules with quite exotic bonds – 2 electrons spread over three atoms for example and none of these meet the octet rule. Subsequent sections will give more information about these and how to judge when they will form.

None the less – the octet rule is extremely useful way to start thinking about molecules and students should always begin thinking about bonding with this rule, but be prepared to deviate from it if needed.

“Copyright Simon Colebrooke 3rd December 2025″.

Suggested next pages:

Alternatively, click the icons below to either return to the homepage, or try a set of questions on this topic (choose the Q icon) or return to the notes menu (N icon).

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk