Learning about electron energy levels is usually one of the early things that students study in A-level chemistry. It is often also one of the more surprising, as ideas about electrons in shells that were developed during earlier stages of education are significantly modified. So you may well wonder what on earth is the evidence to back all this up?

One important source of evidence is the measurement of the amount of much energy needed to remove electrons from their atom – described by the quantity “Ionisation Energy”. There are different ways of thinking about the ionisation energy and this section will introduce a relatively straightforward model and describe what that shows us about the removal several electrons from the same atom. Later sections will develop other approaches and consider trends in ionisation around the periodic table.

Defining ionisation energy

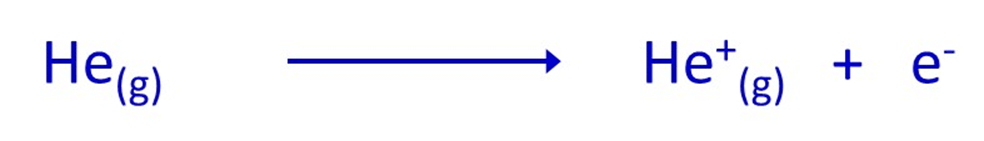

The ionisation energy measures the amount of energy needed to remove a particular electron from an atom. Remember that atoms are electrically neutral because a) they contain an equal number of protons and electrons and b) because these particles have exactly equal but opposite charges. Removing an electron from an atom will therefore form a positive ion, as the remaining part of the atom will now contain more protons than electrons. To illustrate the point, think about what happens when an electron is removed from quite a simple atom – a helium atom:

Initially, the helium atom would have 2 protons and 2 electrons (in helium-4 there are also 2 neutrons but they are neutral and so don’t influence any charges). The combined positive charge of the protons is exactly balanced by the negative charges of all the electrons.

However, if an electron is removed, the remaining part of the original helium atom will still have 2 protons, but only 1 electron. The negative charge of the remaining electron is less than the positive charge of the protons and so there is an overall positive charge – it is a positive ion. The diagram shows the particles involved and their charges.

The equation below represents what has happened:

To allow comparisons with equivalent processes in atoms of other elements the energy is measured with all atoms and ions in the gas phase.

Finally, the amount of energy required to remove an electron from a single atom is extremely small, so instead, the total amount of energy required to remove an electron from one mole of atoms (i.e. 6.02 x 1023 atoms) is reported in units of kJmol-1 (kilojoules per mole).

Thus, the first ionisation energy can be fully defined as:

The energy required to remove one electron from every atom of a mole of atoms in the gas phase, to form one mole of gaseous ions with a single positive charge.

In equation form, “X” is often used to represent an atom of any element:

However, whatever atom is ionised by having an electron removed, what remains is a positive ion, because it always contains 1 more proton than electron.

The hydrogen atom

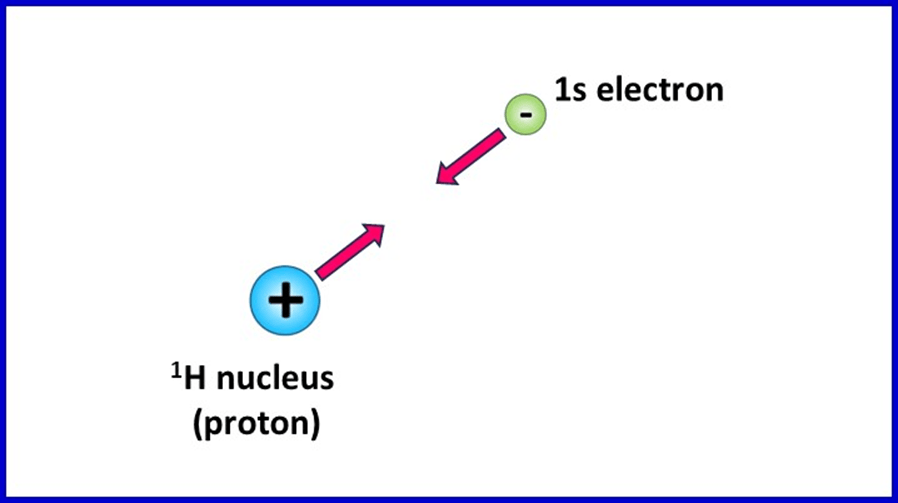

The easiest way to begin understanding this topic is to think about the electrostatic forces experienced by electrons in atoms. If we think about the simplest of all atoms – hydrogen – we can quite easily see why energy is always needed to remove electrons. Atoms of the 1H isotope consist of a nucleus with only one proton and a single electron in a 1s orbital.

The fact that the nucleus and electron have opposite electric charges mean the electron is attracted to the nucleus. To remove the electron means overcoming the attractive force, which requires energy. The situation for a single electron and single-proton nucleus of a 1H atom is shown below, with the direction of the electrostatic force on each particle indicated by an arrow:

The ionisation energy of hydrogen is 1312 kJmol-1. If we divide this value by Avogadro’s constant, 6.02 x 1023, we find that the energy to remove one electron from a single atom is 2.178 x 10-21 kJ or 2.178 x 10-18 J.

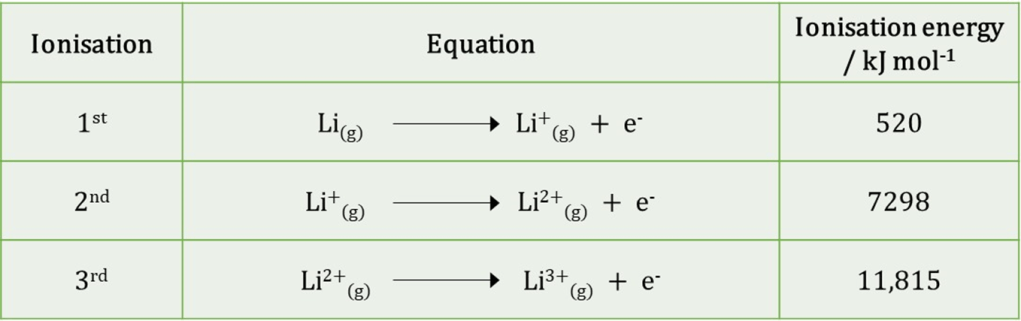

Successive Ionisation Energies

For atoms with multiple electrons it is possible to remove one electron after another and measure the energy required each time. As each electron is removed, the charge on the remaining ion becomes increasingly positive. The different ionisations can be defined like this:

Second ionisation energy: The energy required to remove one electron from each ion in a mole of gaseous ions with single positive charge, to create one mole of gaseous ions with double positive charge. Represented in an equation:

Note that for the second ionisation energy the atom has already be ionised once.

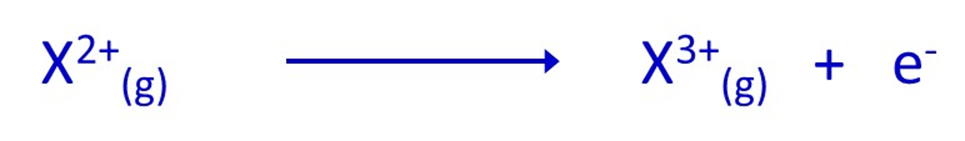

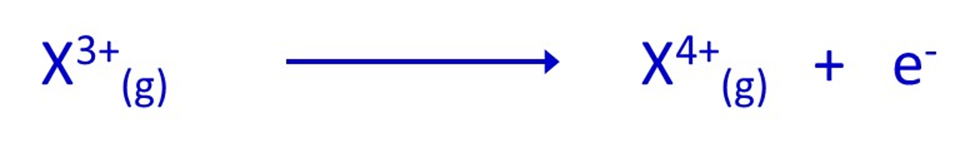

Equivalent equations can be imagined for subsequent ionisation energies:

Third ionisation energy:

Fourth ionisation energy:

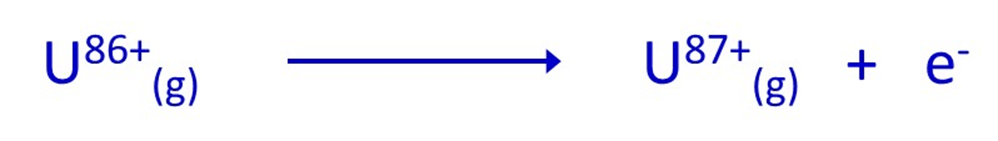

Notice how the ionisation number indicates the positive charge on the ion that is formed, so that it is possible to define (for an element with large atomic number) something like the 87th ionisation energy of Uranium which forms U87+(g) ions:

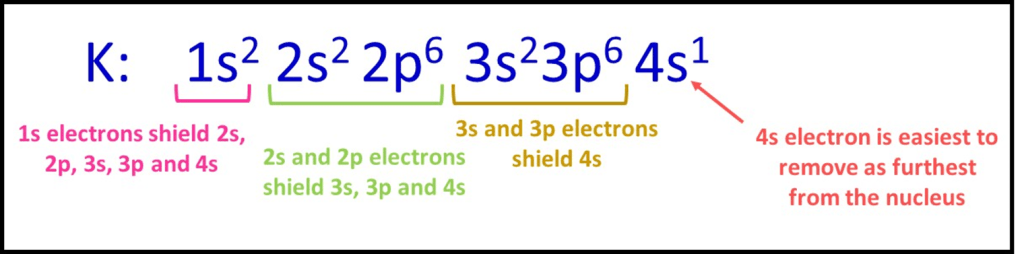

Which electron is lost first from larger atoms?

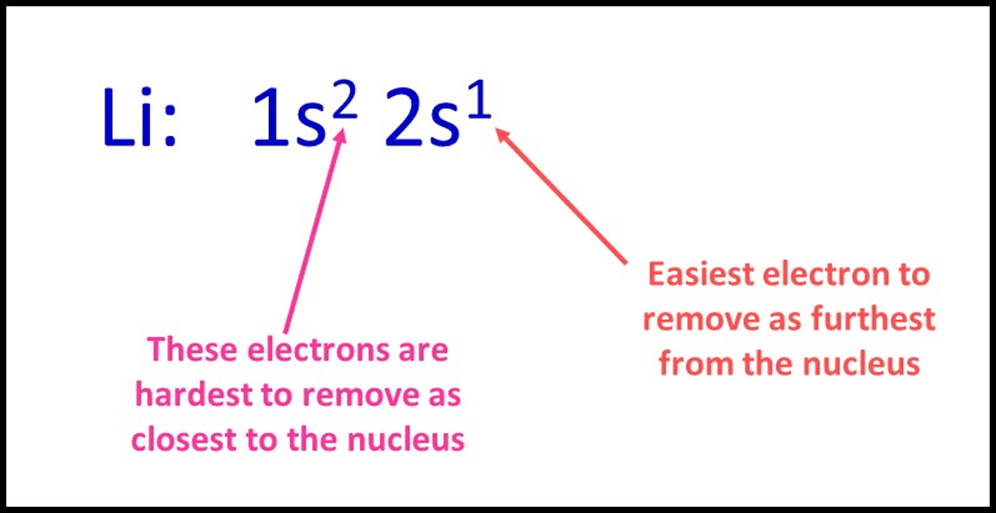

If an atom has several electrons, which one can be removed most easily? This is relatively simple to understand, by thinking about which electron will experience the weakest attraction to the nucleus – that electron will be the easiest to remove.

To start, we can think about lithium atoms which have three electrons in total; two are in a 1s orbital and one is located in 2s. Remembering that, on average, electrons in a 2s orbital will be further from the nucleus than those in 1s, it makes sense that the 2s electron will experience a weaker attraction to the nucleus and be removed most easily.

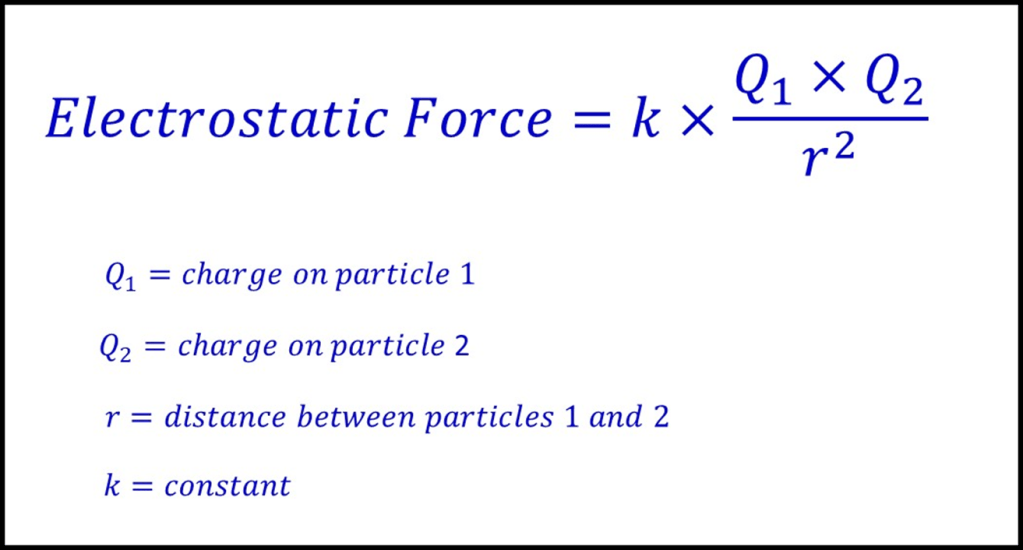

The equation below is “Coulomb’s Law” and can be used to calculate the size of the force between two charged particles. It gives us a way of understanding the factors involved with ionisation, although we cannot take it too far as the Law relates to two stationary charges (and so not something as complex as a multi-electron atom). Never-the-less it is quite useful:

The equation shows that the force between an electron and the nucleus will decrease as the distance between them increases. In fact, the force will decrease very significantly as the electron gets further away because the equation involves division by the square of the distance. This means that doubling the distance reduces the force by a factor of four.

This dependence on distance makes sense of the different ionisation energies for lithium, which are summarised in this table:

We can see that much less energy is needed to remove the first electron than either of the others. The first electron to be removed comes from the 2s orbital, which is furthest from the nucleus and thus, experiencing the weakest force.

So in general, when we look at the electron configuration of an atom, we should expect the electrons to be removed in order from the highest energy subshell to the lowest. We’ll look at this in more detail in subsequent sections. For lithium this means:

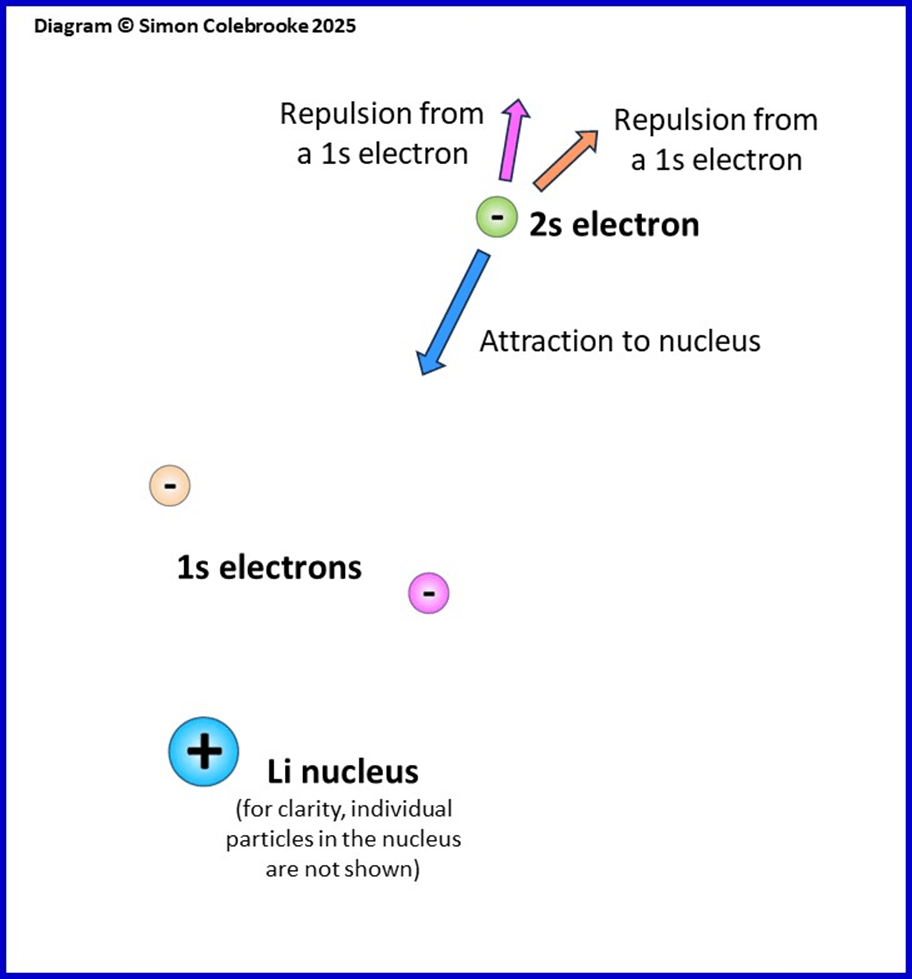

Shielding

However, there is another factor to take into account when considering which electron is easiest to remove from an atom. All atoms apart from hydrogen atoms have multiple electrons and this means that the electrostatic forces they experience are more complicated; as well as an attraction to the nucleus there are repulsive forces between all the electrons. The image below shows the situation for a lithium atom (three electrons in total), with arrows indicating the possible directions of all the electrostatic forces on the 2s electron.

The 2s electron experiences an attractive force pulling it towards the nucleus, plus repulsive forces pushing it away from the two 1s electrons.

The first ionisation energy is 520 kJ mol-1 so energy is still needed to remove the 2s electron. This means that the electron-nucleus attraction is greater than the combined

electron-electron repulsions. However, the repulsions reduce the size of the overall electrostatic force pulling the electrons towards the nucleus. This is often referred to as “shielding” as if the inner electrons are blocking the outer 2s electron from experiencing the full attraction of the nucleus.

The shielding effect that a given electron experiences is almost entirely caused by electrons from lower energy shells . This is because electrons in lower energy shells are, on average, closer to the nucleus and so it is these that have most effect in cancelling some of the nuclear charge. There is relatively little shielding effect between electrons in the same sub-shell or a lower energy sub-shell within the same shell.

Successive Ionisation Energies

Finally, we will see the implications of the factors described above if we compare the ionisation energies of one atom, as one electron after another is successively/consecutively removed. A few examples will illustrate the main points:

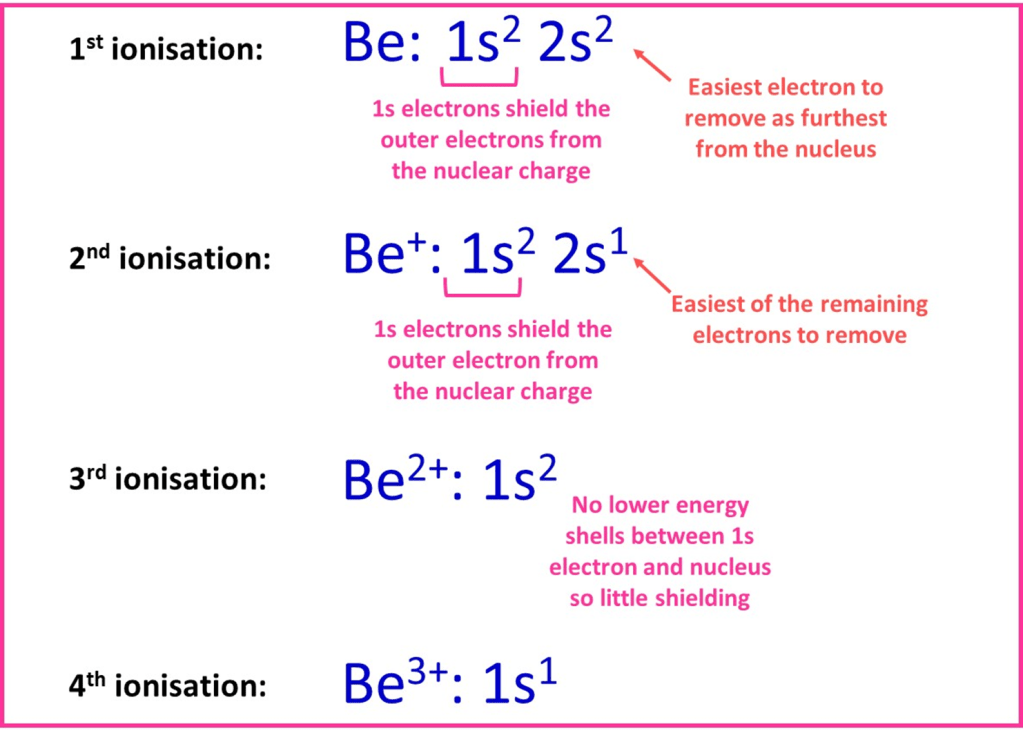

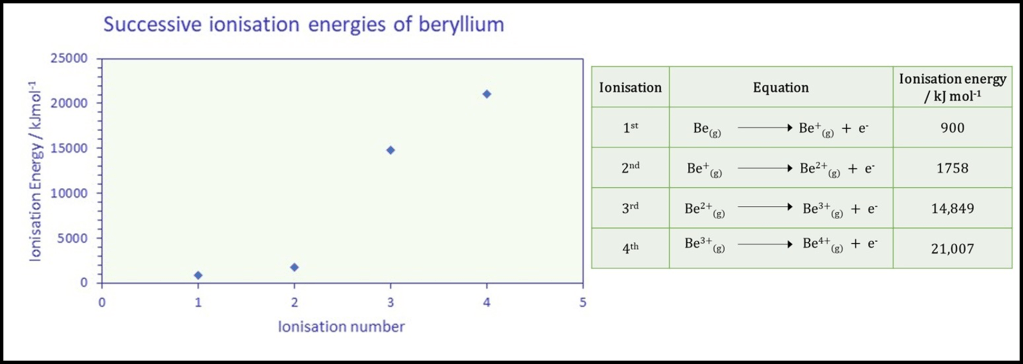

A). Beryllium

Beryllium atoms have four electrons arranged in orbitals as 1s22s2. These can be removed in a series of four successive ionisations. Based on the discussion above we’d expect an electron from the 2s orbital to be the easiest to remove, as the distance from the nucleus is greatest for these electrons and they are shielded by the 1s electrons. The diagram below summarises the electron arrangement from which each successive electron will be removed and the change in shielding that occurs.

The graph and table below displays the energy required in

kJ mol-1 for each successive ionisation.

Here are some important points to note:

1. Each successive ionisation energy is greater than the previous one, indicating that more energy is always needed to remove the next electron. This is due to the fact that each time another electron is removed it is from a ion with increasingly positive charge and the net attraction to the nucleus is greater. It will be harder to remove a second electron from the Be+ ion due to the overall positive charge.

2. The increment between successive ionisation energies is not constant. There is an increase of about 1000 kJmol-1 between the first two ionisations, but then a dramatic increase of around 13,000 kJmol-1 for the third ionisation.

For beryllium, the first two electrons are removed from the 2s sub-shell; furthest of the occupied subshells from the nucleus and shielded by the inner 1s electrons. The third electron will be removed will be from the 1s orbital – it is closer to the nucleus and there is no inner shell to cause shielding. Both these factors mean the electrostatic attraction to the nucleus is much stronger and, hence, a lot more energy is needed to remove the electron.

3. The fourth electron is particularly hard to remove – the ion has an overall 3+ charge and there are no electron-electron repulsions. The attraction of the final electron to the nucleus is much stronger than all of the others resulting in a very high 4th ionisation energy.

Analysis of the graph above shows some particularly useful features that we can later try to recognise in ionisation data from other types of atom:

i) We observe a huge increase in successive ionisation energy when the next electron is removed from a shell closer to the nucleus- between the 2nd and 3rd ionisation energies in the case of beryllium. Hence if you analyse successive ionisation data for an unknown element you can identify where electrons are removed from a new shell by finding very large changes (“jumps”) in the ionisation energy.

ii) We can count the number of “relatively easy” / “low energy” ionisations (though all require some energy) before the first significant increase occurs as this indicates the number of valence shell electrons; two in the case of beryllium.

These two features are indicated on the graph below:

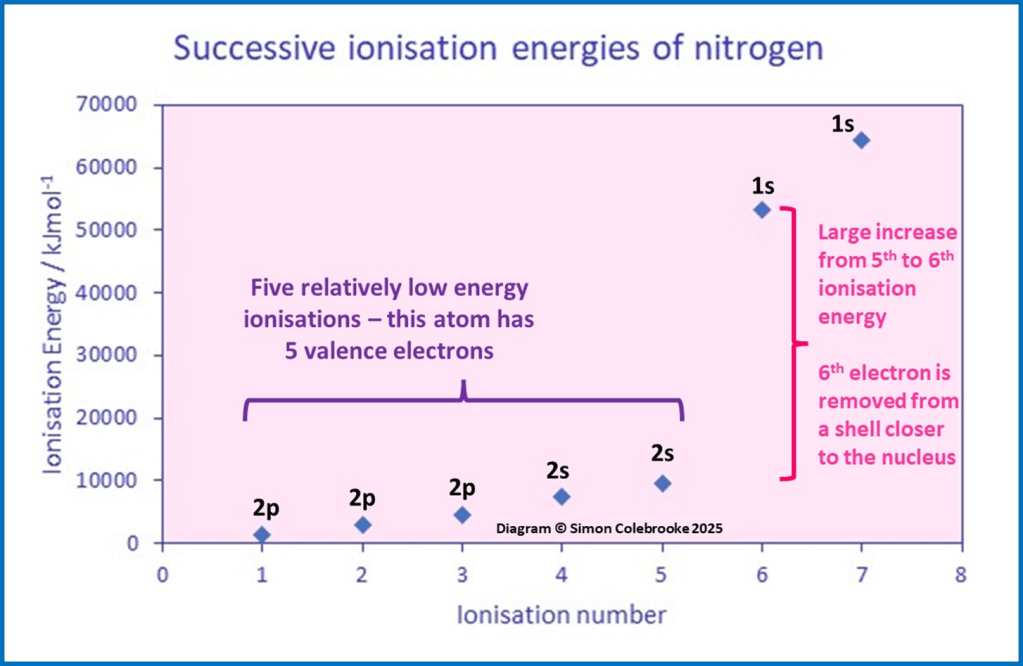

B). Nitrogen

A nitrogen atom has seven electrons in total, arranged as 1s22s22p3. There can be seven successive ionisation energies, as indicated on the graph below, each ionisation labelled with the subshell the electron is removed from:

Now, look for the same type of features in the nitrogen data as we did for beryllium; where large jumps occur and the number of relatively low energy ionisations before those jumps. It is clear in the graph that a large jump occurs between the 5th and 6th ionisations – the sixth electron to be removed is from a shell closer to the nucleus, with less shielding than the first five electrons. Also, the presence of 5 relatively low energy ionisations before the jump shows 5 valence electrons – exactly as predicted for nitrogen.

Notice that there is not a huge change in ionisation energy when electrons are taken from a new subshell within the same shell i.e. in the case of nitrogen, the first electron taken from the 2s subshell after the third electron from 2p. This is the fourth ionisation of nitrogen and there is no associated large jump in energy. This is because firstly, the change in distance from the nucleus does not change all that much between 2s and 2p and, secondly, the is very little shielding between electrons in different subshells of the same shell. The effect of a subshell change is quite small compared to a change in shell, so is not particularly noticeable for successive ionisations in one atom.

However, we will see in a later section that the effect of subshell changes is apparent when 1st ionisation energies are compared for different elements in periodic trends.

C). Potassium

As a final example, potassium has 19 electrons, arranged as 1s22s22p63s23p64s1. As the electrons are now spread across 4 shells, there are going to be 3 large changes in successive ionisation energy as the electrons are taken from new shells. These appear at the 2nd, 10th and 18th ionisation. There is only 1 relatively low energy ionisation at the start, corresponding to the 4s1 electron being removed. After that, electrons get closer to the nucleus and the amount of shielding decreases each time an electron is taken from the next inner shell.

The graph shows how the 19 successive ionisation energies compare for potassium:

The range of ionisation energies for potassium is so great this graph (from 419 kJmol-1 for the first ionisation energy to 476,000 kJmol-1 for the 19th ionisation energy) that I have had to plot the logarithm of the ionisation energy on the y-axis so that the trends can be clearly seen. Eventually, there will be a maths section in these notes, if you need a reminder of what this means.

Final thought

It is worth contrasting the idea of ionisation energy with a common phrase often – and incorrectly – stated by new

A-level students which goes something like this:

“Potassium (or sodium, calcium, magnesium etc) wants to lose electrons to get a full outer shell”.

One reason this is wrong is that the group 1 and 2 elements like potassium still have a first ionisation energy of a few hundred kJmol-1. It still takes the input of some energy to remove electrons from those atoms. If they were going to spontaneously lose electrons no energy would be needed at all. Lumps of potassium and sodium metal will sit in a chemical store for many years without losing any electrons (so long as they are kept under oil and out of the way of water and oxygen). So I think the quote reflects the well known fact that these metals are very reactive. However, the ease with which they react is not simply a consequence of how readily the atoms lose electrons, but how much energy will be released over an entire reaction process, which involves some atoms losing electrons, others gaining electrons, and the resulting ions forming new bonds. A reaction is actually very complicated and ionisation is just a part of it. That is also why definitions matter – the definition of ionisation energy is very specific about things like physical state, ion charges and the quantity of atoms involved – so that later, we can predict things like which elements will react in certain conditions and what types of compound they will go on to form.

“Copyright Simon Colebrooke 1st October 2025″

Suggested next pages

Continue reading about ionisation energy and trends in the periodic table in section 2.

References

I have taken all the ionisation values quoted here from the Wikipedia page “Molar ionization energies of the elements“, which has been an excellent resource for me whilst writing this section. I have rounded all the values to the nearest kJmol-1. If you like ionisation energies you should to spend a while browsing the data on that page – I find it fascinating!

chemistryexplained.uk

chemistryexplained.uk